“Getting Up” is a new story by Oliver Munday, an associate creative director for The Atlantic. To mark the story’s publication, Munday and Katherine Hu, an assistant editor for the magazine, discussed the story over email. Their conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

Katherine Hu: In your story, “Getting Up,” a father, Haiden, struggles with losing his identity to parenthood. He begins to rediscover his sense of purpose by returning to an activity of his youth—graffiti. What drew you to this art form?

Oliver Munday: I, very much like Haiden, used to write graffiti as a kid. The simple answer is that graffiti infuses art and expression with transgression. The danger inherent to the act is addictive. It’s sexy and exciting. Coming up with a unique tag can be thrilling, because you’re hinting at an alter ego through its signature and leaving traces of it everywhere—an alter ego that could be anyone. There’s a romantic mystery to it all—going out under the cover of darkness to make your mark on the world. Needless to say, as an overeager teenager, when a true sense of danger set in, I abandoned all hope of becoming infamous. I was too cloistered for that level of risk.

Hu: The central tension of the story is this desire to maintain a sense of self, even as you start to build a family. Is this possible? Will Haiden eventually succeed?

Munday: It’s not impossible, but it’s not at all easy. Parenting requires so much selflessness, especially with young kids, that it can often feel claustrophobic. Everything around you shrinks. It’s easy to lose touch with interests, and they can simply fall away, making it hard to maintain the parts of your character that comprise your individuality. But there’s also a sense of nobility in pouring yourself into your role as a parent—which can be life affirming, inspiring, and humblingly thankless. A negotiation has to happen in order to balance these inner multitudes. This is what Haiden starts to understand. I think he realizes, at some point, that in order to show his daughter, Carter, the world as he sees it, he needs to get reacquainted with the part of himself that he’s lost touch with. It’s important for him, and ultimately not selfish. She deserves to know.

Hu: The story opens with a stretch of dialogue where Haiden is being woken up by his young daughter. Dialogue dominates throughout, and in scenes with Haiden’s neighbor, Tony, seems to reflect the protagonist’s inner monologue. When is dialogue more useful than narrative?

Munday: Dialogue is always action. Speech lets readers watch characters assert themselves. Sometimes these assertions are at odds or in conflict with the narrative surrounding them, and that friction can be important. Dialogue allows for surprise, humor, and human messiness. In the case of this story, dialogue was most useful when building the father-daughter relationship. The bluntness of children’s speech can often be revealing, and hilarious. When my daughter, Lilly, was just 2, she started calling me Pizza Boy.

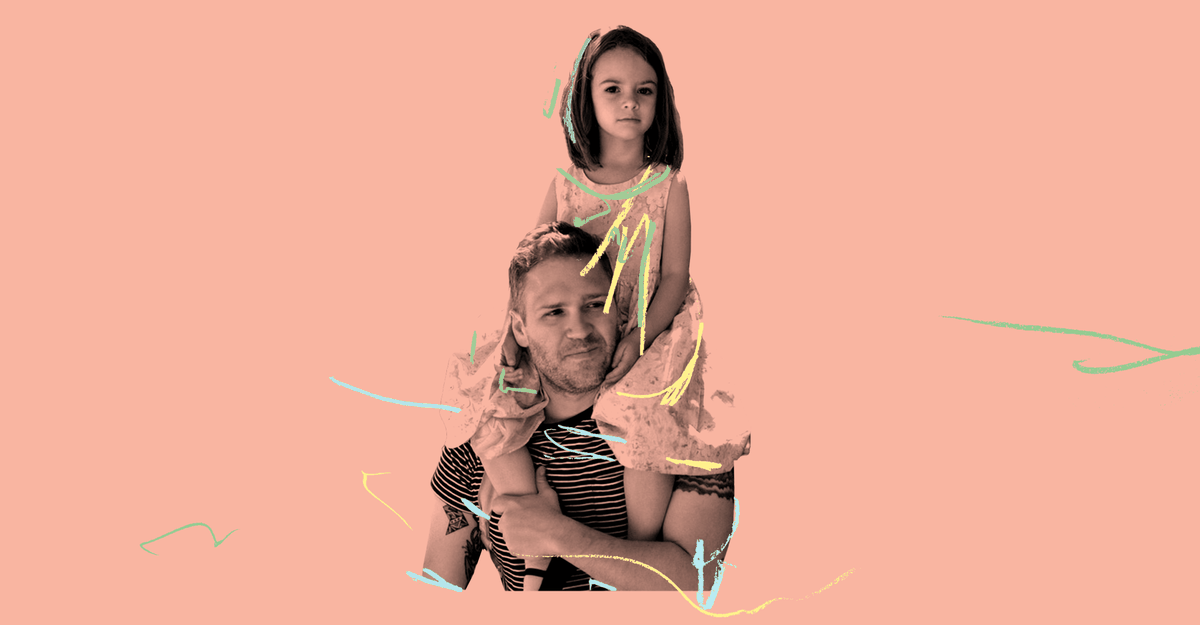

Hu: Writing is not your only creative outlet; you also design and illustrate here at The Atlantic. For those who haven’t already noticed, you also did the art for this short story. Tell me about how you approached that process.

Munday: Writing is a newer outlet for me. The process of writing and editing this story was actually much more labor intensive and creatively demanding than the art was. This meant that for once, I could take a load off when it came to the visuals and be my own kindest critic. What was so satisfying about the process was that the act of making the art became an extension of the story. I used spray paint to make both pieces and made a mess in my apartment. My daughter was around for some of it too. I wanted to deface something, to capture some of the texture—both literal and metaphorical—of graffiti. It was important to me from the beginning that the art for the story be physical; it allowed me to more fully inhabit the fictional world.

Hu: I found myself immersed in the physicality of the story—the shaking of the spray-paint cans, Carter’s toy coin in Haiden’s palm, even the way the marker from Carter’s drawing board is described. How did you envision the physicality resonating with the reader?

Munday: I’m glad you felt that way. Images were the first aspect of writing that I latched onto. It’s no coincidence: I think visually—I’m a visual learner—and this informs the way I move through the world, the way I understand it. As a reader, too, I’m always struck by precise visual descriptions. They take on weight and become grounding. To evoke a sense of touch and feeling is a visceral way to make a connection.

To be a parent is to come into contact again with the wonder of experiencing objects in the world for the first time. Haiden is close enough to this phase of life through Carter that his own sense of wonder has been restored a bit. She helps him see the texture of the world. My daughter, Lilly, did the same for me.

Hu: After his first graffiti escapade, Haiden discovers that his tag looks less impressive in the morning light. His dissatisfaction with his job and marriage offer us a character who “feels pathetic” and, by the end of the story, is just beginning to find his way. How do you keep readers invested in a character with uncertain belief in his own story?

Munday: As a person, I’m racked with uncertainty. This is a relatable-enough quality, but I think my own brand of it involves more than a little self-pity and some indulgence too. I have a close friend who is often bracingly honest, and he has called me out for this. The more I consider it, though, the more I understand that my self-loathing and sustained despondency both act as a convenient way to justify inaction. That pattern can negatively affect the people around you, which I think is very true in Haiden’s case with regard to his wife, Hannah. It becomes a burden for her. The grit required to change, to evolve, to act, is hard won. But it is necessary. Haiden is only beginning to understand this. That we are capable of transfiguring our pain and sadness into beauty makes writing—and all art—thrilling. I hope readers recognize the possibility in this idea, and the truth that few things are ever fixed.

Hu: What new projects are you working on?

Munday: I’m currently elaborating on the themes in “Getting Up,” working on a collection of stories that approach fatherhood, as a subject, from many differing angles. It’s something I continue to wish I could find more of in fiction—fatherhood as a central concern. I’m also working on some design and memoir writing, along with actually designing from time to time. It’s my day job, after all.

"story" - Google News

October 15, 2022 at 06:00PM

https://ift.tt/FJIGcEZ

Oliver Munday On His New Story, ‘Getting Up’ - The Atlantic

"story" - Google News

https://ift.tt/9ZNEHdY

https://ift.tt/l2oEcWj

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Oliver Munday On His New Story, ‘Getting Up’ - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment