The last World War I American “doughboy” died in 2011, at age 110. Of the 2.8 million Yanks who served overseas, 53,402 were killed in action; 63,114 succumbed to disease.

Memories fade, as their children pass on.

Not so Pvt. John Clark Duffy, whose assignment in Motor Transport Company F314 was to drive ammo from the “dump” in rural France to the front lines.

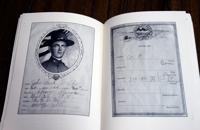

“He never told me a thing about the war,” says this soldier’s son, 84-year-old Southern Pines resident Patrick Duffy. Yet the young enlistee’s story lives on in a transcript of a diary his son expanded, with explanatory notes, into booklet form.

Patrick Duffy, of Southern Pines, with the collection of items, clippings and mementos he included in the World War I diary about his father John Duffy.

Patrick Duffy’s latent interest in genealogy came alive in the 1990s. Home from worldwide postings in the U.S. Foreign Service, he and wife Carol Duffy — also a foreign service officer — visited his sister in Illinois.

“I started asking questions,” Patrick Duffy says. He learned that after being discharged from the Army in 1919, their father, a farm laborer with a grade-school education, had returned to Iowa where he commenced a 40-year career with the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad.

Subsequently, Patrick Duffy attended a reunion, where he discovered “how people fit into the family.” The clan met up at the local cemetery to connect the dots, beginning with Irish-immigrant grandparents.

Patrick Duffy also learned that genealogy can be addictive.

During this time, his sister — keeper of family documents — mentioned having their father’s small government-issue notebook with lined pages, a photo in uniform and quotes from President Woodrow Wilson. Patrick Duffy took it — but did nothing for 20 years.

Finally, in 2019, when Carol was at work and Patrick home alone, he decided, “I’m gonna do it.”

Who knows what he might glean about the months his father spent near French battlegrounds — and never mentioned?

Deciphering the faded script proved daunting. Help came from a third generation.

“My son in Denver is a cartographer,” says Patrick Duffy. “I’d send him stuff, and he’d verify locations.”

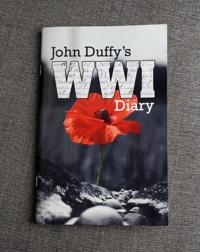

Patrick Duffy's grandson, also named Patrick, created the cover for the book.

The most visible contribution originated with a fourth generation, Patrick Duffy’s 14-year-old grandson, also named Patrick, who designed the haunting cover: a giant poppy sheltering a trench with only the doughboys’ metal helmets visible. The bright red poppy contrasts to the dismal gray warscape. Pvt. Duffy’s handwriting is superimposed on the enlarged letters “WWI.”

Since 1921, poppies — inspired by the poem “In Flanders Fields” — have represented war casualties. Crepe paper poppies are still distributed by military organizations on Veterans Day.

Contents of the booklet, while fascinating, are often mundane. Twenty-four-year-old John Clark Duffy enlisted in the U.S. Army on April 25, 1918. His first entry was June 7, 1918, during basic training at Camp Mills in New York, where he lived in tents, attended Mass and endured all-day drills, but got away evenings for a ball game or dance. After his troop ship sailed on June 28, commentary shifts to seasickness and food.

June 30: Feeling better. The sea is smooth but the grub is putrid. Had fish for dinner that was half rotten. Have boat drills twice a day. Had Mass aboard ship.

July 1: Spent my last cent this morning…the canteen is making a killing … A cup of coffee and a piece of cake costs 15 cents.

July 4th: Very lonesome Fourth. Not even a good feed and no money to buy one. The Battle Cruiser fired … 21 guns. It sounded like the real thing on this smooth sea.

By July 9: In the danger zone …The destroyers all around. Everyone sleeps with their clothes on. Can see the Irish coast.

After landing in Liverpool, soldiers were sent to “rest camps” before traveling through England by train. “The trip was great.”

On crossing the English Channel to Cherbourg: “It sure was rough. Nearly everyone was sick.”

Once in Bordeaux (by train, standing up) his unit was quartered in an old farmhouse where the water had been condemned.

July 23: Went to Mass in an old French church ….r eceived communion.

July 28th brought some r-’n-r: Went downtown in evening… Me, Joe Martin and Roach had a big time in orderly room after we came back.

Roach? Nicknames are big in wartime, a la Hawkeye and friends of “M*A*S*H.”

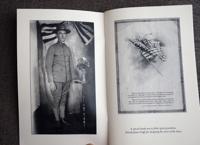

A photo of John Clark Duffy as he prepared to head to Europe during World War I

Beginning in October, John Clark Duffy’s tone turns serious, with a 10-mile march ending in encampment near the front lines: The Huns have shelled us nearly every night but never hit us. One or two shots came close. The airplanes try to locate us but get driven off.

A chance encounter, not unusual in the military: Coming back to Company I met a fellow from Clinton, Iowa. He knew the Foleys of Dixon.

John Clark Duffy’s entries grow longer, as he describes side trips to French villages and building a tin-roofed hut with stove, which he describes as … Very comfortable for the nights are quite cold. Everyone is talking about the new peace offer. Some of the boys think we will be home for Christmas. But not me.

By late October, he was experiencing the real thing:

The drive has started…it sure was a wild night….the whole sky was one blaze of fire and the noise was terrible. The Huns (Germans)…hit all around us but never the ammo drop, which was their objective.

He describes a barrage of machine gun fire but no one got hurt.

The diary ends abruptly on Nov. 6, 1918, perhaps because Pvt. Duffy contracted the mumps, also the Spanish flu during the global pandemic. He returned stateside on April 2, 1919, and was discharged three weeks later.

What son Patrick Duffy finds missing is any mention of fear. His father calls battles “the big noise” without noting casualties. “No gory details … that surprised me.”

Perhaps as a driver and later, a mail orderly who delivered to the front, he did not experience combat. Perhaps attending Mass helped; once home, Patrick Duffy became an active member of Knights of Columbus.

During World War II, Patrick Duffy, now married with children, served as a civilian air raid warden.

John Clark Duffy died in 1965. His three sons served in the military in Japan, Korea and Germany.

Deciphering the faded script took four months. Patrick Duffy’s wife and daughter helped edit and proofread. Fifty copies were printed and distributed to family at a birthday celebration where, Patrick Duffy says, “It caused a sensation. All the kids read it, cover to cover. Nobody had a (cell) phone out.”

Patrick Duffy, now retired from a career spanning the globe, is visibly proud to have honored his father’s service.

“It made me feel much closer to him,” he says, adding that it brought forth other stories from the family, like the time his father gave ice skates to nephews, but a doll to his niece, who would rather have skated with her brothers.

Today, Patrick and Carol Duffy will attend an annual Veterans Day luncheon hosted by Table on the Green in Pinehurst. Patrick will also participate in a flag raising at Knollwood Village. Finally, he will re-read his father’s handwritten account of taking part in the Allied effort a hundred years ago, far from home.

"diary" - Google News

November 12, 2020 at 01:22AM

https://ift.tt/3kg0Fuo

'Destroyers All Around': Southern Pines Man Transcribes Father's Diary Entries From World War I - Southern Pines Pilot

"diary" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VTijey

https://ift.tt/2xwebYA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "'Destroyers All Around': Southern Pines Man Transcribes Father's Diary Entries From World War I - Southern Pines Pilot"

Post a Comment