In late December 2020, Chief Superintendent Sharon Brown hung up her blue uniform for the last time after serving in the Division of Identification and Forensic Science (DIFS) of the Israel Police for 31 years.

Brown spent 23 years as a documents examiner, and then served as head of the lab from 2012 to 2017. In the last three years of her tenure, she was head of research and development at DIFS. Starting out as an inspector, she rose through the ranks to a senior officer position.

“I’m enjoying the newfound relaxation, but I’m open to ideas and offers for what to do next,” laughed Brown, who was accustomed to long, busy days at the questioned documents laboratory at the Israel Police National Headquarters in Jerusalem.

Brown’s most high-profile forensics work involved reassembling and visualizing the erased writing of the miraculously salvaged notebook belonging to Israeli astronaut Ilan Ramon, who was killed in the 2003 Space Shuttle Columbia disaster. She also recovered the words of slain teen Gil-ad Shaer, whose damaged diary was retrieved from the burned car of the Hamas terrorists who kidnapped and murdered him, along with Naftali Fraenkel and Eyal Yifrach in 2014.

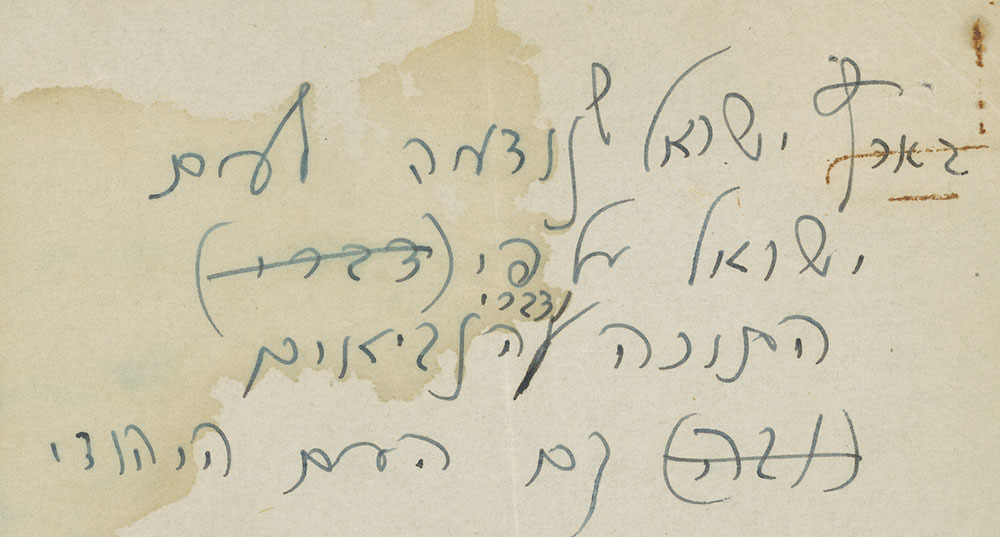

A page from Gil-ad Shaer’s recovered diary. (Courtesy)

Shaer’s mother Bat-Galim Shaer became friends with Brown through the process of working together on the diary.

“Sharon accompanied us through a difficult time. She was very sensitive, responsive and humane. She’s professional and serious, but also very warm,” Bat-Galim Shaer said.

In a recent interview with The Times of Israel, Brown spoke about these major accomplishments, as well as her other work over the years.

“I will never forget these two cases. It was an honor and privilege to work on them,” said Brown, reflecting on the emotional as well as the technical challenges involved.

Although she was sometimes called to testify in court, the public for the most part was unaware of the behind-the-scenes impact of her expertise in scientific examination of documents, including identity cards, drivers licenses, passports, checks, Holocaust documents, archeological artifacts, and old maps.

The official retirement age for members of the Israel Police force is 57, but Brown stayed on an extra year to wrap things up. At 58, she looks back on her service with satisfaction and pride. She is especially pleased with the trail she blazed as a native English speaker, and a woman, on the force.

The remains of Israeli astronaut Ilan Ramon’s diary that went on display at the Israel Museum, May 21, 2019. (Ramon Family Foundation Facebook page)

“I was a ‘different kind of bird’ at work with my English cultural mannerisms. It was noticed, and not always positively. But I embraced it, and I believe I made an important cultural contribution. I would definitely encourage other ‘Anglos’ to apply to the force,” Brown said.

A married mother of four daughters in their 20s, Brown was born and raised in London in a Modern Orthodox family. Her father was a refugee from Munich, Germany, and her mother a refugee from Trieste, Italy, who arrived in Palestine in 1939 on the last boat allowed in by the British. The two met in Tel Aviv and married in 1946.

After the birth of their first daughter, Brown’s parents moved in the early 1950s to Japan so that Brown’s father could work for Israeli mogul Shaul Eisenberg. The family set up house in Tokyo while Brown’s father worked mainly in South Korea. Two more girls were born in Japan, and Brown — the youngest — was born in London after the family relocated there almost a decade later.

Sharon Brown (third from right) with her husband, four daughters, and one of her sons-in-law. (Courtesy)

Brown spent summers visiting extended family in Israel, and decided to immigrate after high school. It was a natural choice, with her older sisters having all done the same. Following a year of national service, Brown pursued undergraduate and graduate degrees in chemistry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

In 1989, Brown initially interviewed for a position at another of the 15 DIFS labs.

“I heard about an opening at the analytical chemical lab and was encouraged to apply by my Hebrew University adviser, Prof. Eli Grushka. I didn’t get that job, but ultimately I was offered a position at the questioned documents lab,” Brown said.

From Ilan Ramon’s diary (Israel Museum)

The lab involves two kinds of work, the first being handwriting examination.

“Handwriting examination must not be confused with graphology,” Brown was quick to note.

“Handwriting-examination professionals do a four-year-long apprenticeship under an expert to gain certification. A graphologist might as well be reading tea leaves or coffee grinds. We have to contend with these people without proper education and experience in court,” Brown said.

The second type of activity at the questioned documents lab involves scientific examination of documents, which is Brown’s expertise. Documents are put under microscopes for examination of printing, inks, erasures and obliterations.

Chief Superintendent Sharon Brown served three decades with the Israel Police before retiring in December 2020. (Courtesy)

The documents are subjected to optical methods allowing them to be looked at under different light sources, which pick up things that are not visible to the naked human eye. There is also the option of using thin-layer chromatography, a chemical method by which a “biopsy” of an ink line is dipped in a solution.

“We prefer not to have to do this, because it destroys the ink line and is irreversible,” Brown said.

Although tight budgets prohibited Brown from attending many international conferences, regular online contact with colleagues around the world helped her keep up with the latest research and advances in her field.

“Don’t forget, when I began, documents were produced in black and white and by typewriters. Today documents are mostly prepared on computers and printed with color inkjet printers,” she said.

Much of Brown’s work involved detecting forgeries — everything from checks to documents related to land cases. In particular civil cases where people presented documents claiming land ownership dating back to the early 20th century, Brown and her colleagues proved they were recently produced and phony.

“Laser printers didn’t exist in 1917,” Brown quipped.

Chief Superintendent Sharon Brown, wearing her signature high heels, with her daughter’s dog. (Courtesy)

One of Brown’s most memorable cases spoke to her love of puzzles. A man pretending to be a psychologist preyed on girls and raped them. The man shredded all incriminating documents, but Brown and her colleagues painstakingly reassembled all of them for the police investigators.

As an observant Jew, Brown did not generally work on the Sabbath or holidays.

“But if I was called in to work on those days, I would go. It was always justified and very important,” she said.

Brown also patrolled the streets of downtown Jerusalem on Friday nights when called to do so. Although she spent most of her time in the lab or behind a desk, she was first and foremost a police officer.

“I went through basic police training, officers training, advanced officers training, and weapons training. I carried a gun when necessary, even on Shabbat,” she said.

The biggest challenge of going out on the beat wasn’t carrying a weapon, but rather having to change her footwear.

“I’m really short, so I always wear high heels. But I opted for sensible shoes when on patrol,” Brown said.

"diary" - Google News

March 19, 2021 at 06:26AM

https://ift.tt/30UaKWH

Trailblazing forensics expert who decrypted Ilan Ramon diary retires from force - The Times of Israel

"diary" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VTijey

https://ift.tt/2xwebYA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Trailblazing forensics expert who decrypted Ilan Ramon diary retires from force - The Times of Israel"

Post a Comment