Friday, October 1, 2021. Partly cloudy, and sunny, yesterday in New York with temps in the mid-60s by day and mid-50s by night. Huge, billowing dark clouds passing through but no rain upon us.

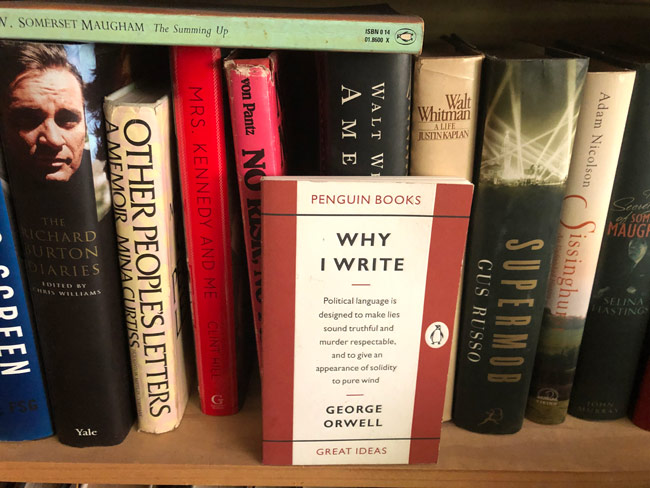

Yesterday, as I was continuing to edit my bookcases to eliminate the problem of too many books and not enough space, I came upon a thin, small paperback by George Orwell titled Why I Write with the sub “Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind”.

I must have had this book for years. I don’t know how I got it although I do tend to buy books (with the intention of reading them, of course) although after the purchase that’s often as far as I get with them. I am a constant reader 8 days a week; can’t resist. This one has been in my pile to departures for so long that I’ve been looking at it uninterested for awhile.

I never read Orwell’s most famous piece, although, I of course, knew about it. I am also aware that his perceptions were accurate and frightening. They are basically, like everything else we do, an aspect of the human personality and its relationship to itself and the environment.

Last night while making my dinner I did some more straightening up with the books when Why I Write really caught my eye again — the explanation personally interesting to me. Because writing and thinking about writing — which I’ve been doing since I was a little boy playing on the Smith-Corona portable typewriter that my mother bought for me (at my personal request) — is where my head goes everyday, almost every hour. It started in early, age 10 or 11. Not the writing part but the part of looking at oneself as objectively as possible.

That was required in my life and my existence from my earliest memories — ages 3 through 9 or 10. I was a troubled child, or rather a child who felt he had serious troubles, living in a household rife with outburst and upsets between my mother and my father. It is curious even questionable to me if indeed I were that young when my “troubles” began.

Anyway, I finally opened Mr. Orwell’s book. Orwell, I learned, was his pen name. He was born Eric Arthur Blair. I don’t know how he came upon it although his nom de plume has a darkish coldness to it. You remember it because it’s serious and to the point.

I do not read political books per se, although I have always been an avid reader of people’s lives. Why I Write turned out to be one of four pieces he’d written over the years for this book. It is not a political piece. His was a short life as it turned out. He was born in June 1903 and died in 1950. And yet some of his work remains modern for three quarters of a century later.

But what interested me about Why I Write was the how he became a writer. I have been a writer since my tenth or eleventh Christmas when I asked my mother for that Smith-Corona portable, and she got it for me. I thought then, as I think now, obtaining that typewriter was a lot to ask for. My mother was a working woman, 9 to 5, five days a week for 35 or 50 cents an hour. With that she fed, clothed and even paid for piano lessons for this kid.

My favorite aunt and uncle, who were business people, had typewriters at their desks and when visiting I was allowed to put the paper in the roll and type on it. I don’t know what the allure was other than being able to print out a word before my eyes. I don’t recall what I typed out back then, but when I got the Smith-Corona, all I wanted to do was write down what I was thinking and what I couldn’t express openly — mainly about what a difficult time this boy was having in young life.

The following is George Orwell in this book:

“I give my background information because I do not think one can assess a writer’s motives without knowing something of his early development. His subject-matter will be determined by the age he lives in — at least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own — but before he ever begins to write, he will have acquired an emotional attitude from which he will never completely escape. It is his job, no doubt, to discipline his temperament and avoid getting stuck at some immature stage, or in some perverse mood: but if he escapes from his early influences altogether, he will have killed his impulse to write.

“Putting aside the need to earn a living, I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living.

“They are: 1. Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grownups who snubbed you in childhood, etc. etc. It is humbug to pretend that this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful businessmen — in short, with the whole top crust of humanity.

“The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they abandon individual ambition – in many cases, indeed, they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all – live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should add are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

“2. Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or a writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.

“3. Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for use of posterity.

“4. Political purpose – using the word “political” in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

“…I am not able, and I do not want, completely to abandon the world-view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well, I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style to love the surface of the earth, and to take pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us.

“In any case I find that by the time you have perfected any style of writing, you have already outgrown it. Animal Farm was the first book in which I tried, with full consciousness of what I was doing, to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole. I have not written a novel for seven years but I hope to write another fairly soon. It is bound to be a failure, every book is a failure, but I know with some clarity what kind of book I want to write.

“… All writers are vain, selfish and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand. For all one knows, that demon is simply the same instinct that makes a baby squall for attention. And yet it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality. I cannot say with certainty which of my motives are the strongest, but I know which of them deserve to be followed.”

DPC: I recorded all of this as a kind of therapy for myself, this writer. I have been struggling inwardly with writing a memoir of my life. This exercise is curious to this writer because I see at this late age that I was able to make a life out of a great deal of personal hardship and with the blessed asset of people who cared for this child. Otherwise, I carry, as Orwell says about himself, a sense of not being a very interesting individual still struggling.

Yet I also have had the experience by this age, of experiencing the pleasure of succeeding to get myself published and taking a serious view of myself rather than one of a simpering, nothing, bore. Although truthfully, I’ve never thought of myself as simpering or boring, although those characteristics are a writer’s sense of character behind the character.

But it has been a lifelong schooling for me. At this time with everything in our world changing faster and faster, I am often challenged in finding material to interest my reader which is the most basic of terms. I write for the reader, to communicate with the reader and lend a sense of an experience or a personality. I do that for my own personal interest in learning about us and who we are and what motivates us in our basic actions and activities.

That boy-child, the 20th century American kid, is still there, but now the old man, still a young one in his consciousness, comes from a different, gentler, fresher world for those of us who were fortunate to have been there.

So, you see that finally getting to Orwell’s words, I found some relief and encouragement from whom I perceive as having been a wise man (and a productive writer).

"diary" - Google News

October 01, 2021 at 05:52PM

https://ift.tt/3D1SgEz

Why We Write - newyorksocialdiary.com

"diary" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VTijey

https://ift.tt/2xwebYA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why We Write - newyorksocialdiary.com"

Post a Comment