By John LastFeatures correspondent

EyesWideOpen/Getty Images

EyesWideOpen/Getty ImagesVisitors to Italy's mountain resorts may not know that with every order of classic bombardino, they are taking a side in one of Italy's longest-standing culinary rivalries.

Hit the slopes at Cortina, Val Gardena or Mottolino, and you'll quickly become familiar with one of Italy's most iconic winter cocktails: bombardino.

Invented in 1972 by Aldo Del Bò, a ski lift manager in Livigno, bombardino mixes whiskey or brandy and hot zabaione, the Italian version of eggnog, finishing it off with a heap of piped whipped cream. It's the perfect drink to warm yourself after a day on the powder – a "small indulgence", in the words of one Italian writer, "with an invigorating power".

But visitors to Italy's mountain resorts may not know that with every order of this now classic cocktail, they are taking a side in one of Italy's longest-standing culinary rivalries – one that dates beyond the founding of the country itself, and weaves into its history a fake 19th-Century chef, the Austrian Imperial court and the frostbitten soldiers of World War One.

The key ingredient of bombardino, zabaione, is older than any of these characters. Recipes for Italian-style eggnog – a mixture of eggs, sugar and fortified wine – date back as far as 1533, when it was served ice cold in the court of Catherine de' Medici.

Ian G Dagnall/Alamy

Ian G Dagnall/AlamyAccording to one legend, these old recipes find their origin in the search for a hearty (and boozy) meal replacement drink for the soldiers of the 15th-Century mercenary, Captain Zvàn Bajòun, whose name inspired the word zabaione. More likely is a simpler story: the drink was invented in Turin to honour the patron saint of pastry chefs, St Paschal Baylón, sometime in the 16th Century.

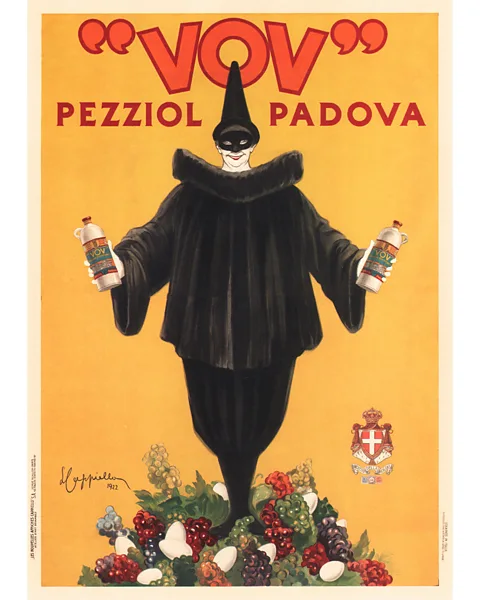

But to make a bombardino properly, not just any eggnog will do. Since its genesis on the ski slopes, the traditional recipe calls for a very specific type of zabaione: VOV. And it's with VOV that the story of Italy's eggnog war – the century-long battle to define the recipe for one of the country's most iconic winter drinks – begins.

VOV has its origins in the medieval university town of Padua, some 50km inland from Venice. Famous for its botanical garden – the first in the world – Padua had long been a site of culinary and medical innovation. With the arrival of Italy's industrial revolution, that reputation was only supercharged.

"[Padua] was a city closed within 16th-Century walls," said Simone Marzari, a researcher who helped write Il CYNAR e I suoi Fratelli (Cynar and its brothers), a history of the company that once produced VOV. "Suddenly, it exploded – and a lot of bars and pastry shops began to open."

The Protected Art Archive/Alamy

The Protected Art Archive/AlamyAmong them was the family grocery of Giovanni Battista Pezziol, who left Venice to settle in Padua in the early 1840s with his brother Giuseppe. Opening a pair of small groceries in Padua's centre, Giovanni soon outshone his brother for his house-made torrone, a classic Italian confection of nougat and nuts.

According to VOV company legend, it was while producing torrone that Giovanni was suddenly struck by inspiration. Nougat required only egg whites, and lots of them, so Giovanni needed a way to dispose of hundreds of leftover yolks. In a moment of genius, he decided to bottle and market his own zabaione, becoming the first commercial producer of the Venetian specialty.

At first, he called his drink "Benedictine Zabaglione", playing on the well-earned reputation of monks for crafting experimental liquors. But soon, he gave it up for a simpler name, inspired by the Venetian word for eggs, "vovi": VOV.

From the moment it first appeared in 1845, VOV was a sensation. Ingeniously marketed by Giovanni's daughter, Maria, as a health drink with restorative properties, it was popular enough to draw the attention of the ruling archdukes of Austria-Hungary, who granted the concoction their seal of approval.

By World War One, VOV's reputation as a health drink was cemented enough that it was prescribed to soldiers with the approval of the Red Cross. This version, with chocolate added for an extra boost, was not VOV, but VAV: an acronym for vino alimento vigoroso or "vigorous food wine" – a meal replacement for combatants just like it was in the day of Zvàn Bajòun.

EyesWideOpen/Getty Images

EyesWideOpen/Getty ImagesIt seemed VOV would forever dominate the world of zabaione – indeed, already its name was becoming synonymous with any Italian eggnog. But behind the scenes, the sun was already setting on VOV's golden age.

Throughout the 1930s, the Pezziol brothers found themselves continually on the wrong side of the law. By 1936, they had been mired in trials for fraud and embezzlement for so long that the company was left bankrupt. Maria was forced to sell to a Pugliese businessman, who in turn sold the brand onto Molinari Distilleries, the makers of Sambuca. They, too, struggled to make the most of the brand – and by 1964, they sold it too, to the makers of a rival cocktail mix, Cynar.

During these struggles, the genuine VOV found itself locked in a battle for customers with a veritable flood of new imitators. Practically every distillery and pastry shop had their own spin on zabaione they could bottle and sell as a rival to VOV. "The fact is, it's a recipe that was… passed along from mother to daughter, among all the poor families of the country," said Antonio Dalle Molle, a descendant of the family that bought the VOV brand in the 1960s.

The main challenger emerged from a family in the city of Ferrara, where Luigi Moccia devised a recipe that swapped marsala wine for brandy. The result was "Zabov", a much sweeter and less alcoholic version. "Zabov was the enemy," Dalle Molle said. But at least initially, "there was no competition. The proportion [of sales] was 1,000 bottles to one."

tatyana_tomsickova/Getty Images

tatyana_tomsickova/Getty ImagesThe real problem, Dalle Molle said, came not in spite of VOV's popularity, but because of it. By the 1980s, VOV had become so popular it was synonymous with zabaione itself. "My family spent a lot of money for the trademark," he said. But soon after they bought it, every zabaione, from the version at the local bar to one scrawled in a grandmother's recipe book, came to be known as VOV. "They'd say, 'VOV was made by my mother' – but it was not VOV!"

Meanwhile, the real VOV seemed to be losing touch with its roots and losing ground to its competitors. Facing flagging sales, Dalle Molle's family eventually sold the brand themselves, and the new company moved its production to Turin – severing its deep connection to its hometown of Padua.

Then, in 2017, one final insult seemed to put a nail in the coffin of VOV's legend. A cookbook, purportedly authored by a Piedmontese chef from the Royal Court of Italy, alleged the recipe for VOV had in fact been stolen by a young Giovanni Pezziol during his apprenticeship. The book was eventually exposed as a hoax – but the damage was done. Zabov surpassed VOV in sales, and the eggnog war appeared to be over.

Today, Dalle Molle says, VOV has been all but "completely forgotten". And it's not alone – dozens of similar brands from VOV's heyday are now out of production or struggling to find a market. Over time, Dalle Molle says, Italy's artisanal liqueurs have steadily lost ground to craft beers, fancy cocktails and the ubiquitous Aperol spritz. Even the comparatively popular Cynar, an herbal concoction invented by Dalle Molle's father, has seen its sales fall precipitously. "In 1974, we sold 24 million bottles," he said. "Now, they don't sell more than four million."

Laurent Fabre/Alamy

Laurent Fabre/AlamyBut while most of Italy seems happy to leave VOV in the 1970s, there is one place where the drink still reigns supreme – in the ski towns of Italy's north.

"At high altitudes, you feel the cold, so you need something to warm up," said Elisabetta Dotto, the locandiera (innkeeper) of the stylish Hotel Ambra in the Italian ski capital of Cortina. When tea or hot chocolate won't cut it, she said, you need "a proper drink – with a high calorie and alcohol content that puts the mind and body back on track".

Today, the Hotel Ambra's Zelda Lounge still sells its fair share of bombardino, the classic cocktail of VOV, brandy and whipped cream. But it's also trying to make its own mark, finding new uses for the forgotten concoction. Its "Warm Your Feet" cocktail mixes VOV with tropical-flavoured syrup and Italian grappa for a whole new take on the zabaione flavour.

If the story of VOV shows anything, it may be this: everyone wins in an eggnog war. Italy has no shortage of new recipes for its beloved zabaione – and no shortage of cold travellers in need of its delights.

BBC.com's World's Table "smashes the kitchen ceiling" by changing the way the world thinks about food, through the past, present and future.

---

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"story" - Google News

December 20, 2023 at 08:00PM

https://ift.tt/fDSc8OP

VOV: Where the story of Italy's eggnog war began - BBC.com

"story" - Google News

https://ift.tt/gK84wLa

https://ift.tt/95rbL74

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "VOV: Where the story of Italy's eggnog war began - BBC.com"

Post a Comment