In the world created by Bond, people come and leave but not before changing the moment forever. (Source: Tashi Tobgyal)

In the world created by Bond, people come and leave but not before changing the moment forever. (Source: Tashi Tobgyal)

If there has been one author who made readers befriend hills and ghosts with equal vigour, it has to be Ruskin Bond. Born on May 19, 1934 Bond has written several short stories for children and in most of them he weaved in an element of intrigue. And in this regard, trains and stations hold great significance. For instance, in the short story, Night Train At Deoli, he stitched love and heartbreak together as a lone platform bore witness. In the world created by Bond, people come and leave but not before changing the moment forever.

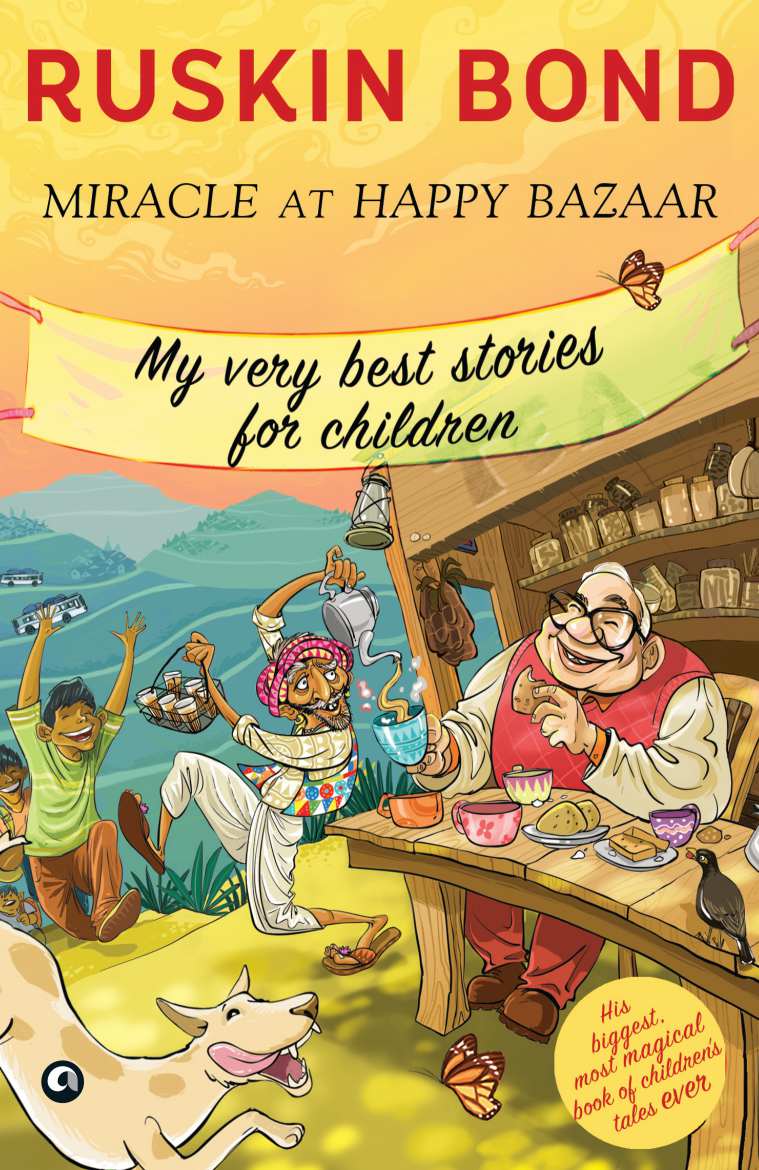

Earlier this month, a collection of his short stories, Miracle At Happy Bazaar, My Very Best Stories for Children was released as an Ebook by Aleph Book Company. Here is an extract from The Woman on Platform No 8.

ALSO READ | Amid lockdown Ebooks emerge as unlikely saviour for publishing houses

Extract

It was my second year at boarding school, and I was sitting on Platform No. 8 at Ambala station, waiting for the northern bound train. I think I was about twelve at the time. My parents considered me old enough to travel alone, and I had arrived by bus at Ambala early in the evening: now there was a wait till midnight before my train arrived. Most of the time I had been pacing up and down the platform, browsing at the bookstall, or feeding broken biscuits to stray dogs; trains came and went, and the platform would be quiet for a while and then, when a train arrived, it would be an inferno of heaving, shouting, agitated human bodies.

As the carriage doors opened, a tide of people would sweep down upon the nervous little ticket collector at the gate; and every time this happened I would be caught in the rush and swept outside the station. Now tired of this game and of ambling about the platform, I sat down on my suitcase and gazed dismally across the railway tracks. Trolleys rolled past me, and I was conscious of the cries of the various vendors—the men who sold curds and lemon, the sweetmeat seller, the newspaper boy—but I had lost interest in all that went on along the busy platform, and continued to stare across the railway tracks, feeling bored and a little lonely.

‘Are you all alone, my son?’ asked a soft voice close behind me. I looked up and saw a woman standing near me. She was leaning over, and I saw a pale face, and dark kind eyes. She wore no jewels, and was dressed very simply in a white sari. ‘Yes, I am going to school,’ I said, and stood up respectfully. She seemed poor, but there was a dignity about her that commanded respect.

‘I have been watching you for some time,’ she said. ‘Didn’t your parents come to see you off?’ ‘I don’t live here,’ I said. ‘I had to change trains. Anyway, I can travel alone.’ ‘I am sure you can,’ she said, and I liked her for saying that, and I also liked her for the simplicity of her dress, and for her deep, soft voice and the serenity of her face.

‘Tell me, what is your name?’ she asked. ‘Arun,’ I said. ‘And how long do you have to wait for your train?’ ‘About an hour, I think. It comes at twelve o’clock.’ ‘Then come with me and have something to eat.’ I was going to refuse, out of shyness and suspicion, but she took me by the hand, and then I felt it would be silly to pull my hand away. She told a coolie to look after my suitcase, and then she led me away down the platform. Her hand was gentle, and she held mine neither too firmly nor too lightly. I looked up at her again. She was not young. And she was not old. She must have been over thirty, but had she been fifty, I think she would have looked much the same. She took me into the station dining room, ordered tea and samosas and jalebis, and at once I began to thaw and take a new interest in this kind woman.

The book was released earlier this year. (Source: Aleph Book Company)

The book was released earlier this year. (Source: Aleph Book Company)

The strange encounter had little effect on my appetite. I was a hungry schoolboy, and I ate as much as I could in as polite a manner as possible. She took obvious pleasure in watching me eat, and I think it was the food that strengthened the bond between us and cemented our friendship, for under the influence of the tea and sweets I began to talk quite freely, and told her about my school, my friends, my likes and dislikes. She questioned me quietly from time to time, but preferred listening; she drew me out very well, and I had soon forgotten that we were strangers. But she did not ask me about my family or where I lived, and I did not ask her where she lived. I accepted her for what she had been to me—a quiet, kind and gentle woman who gave sweets to a lonely boy on a railway platform…

After about half an hour we left the dining room and began walking back along the platform. An engine was shunting up and down beside Platform No. 8, and as it approached, a boy leapt off the platform and ran across the rails, taking a shortcut to the next platform. He was at a safe distance from the engine, but as he leapt across the rails, the woman clutched my arm. Her fingers dug into my flesh, and I winced with pain. I caught her fingers and looked up at her, and I saw a spasm of pain and fear and sadness pass across her face.

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Books And Literature News, download Indian Express App.

"story" - Google News

May 19, 2020 at 02:01PM

https://ift.tt/3cHYDjO

Ruskin Bond’s birthday: An extract from his short story, The Woman on Platform No 8 - The Indian Express

"story" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2YrOfIK

https://ift.tt/2xwebYA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Ruskin Bond’s birthday: An extract from his short story, The Woman on Platform No 8 - The Indian Express"

Post a Comment