Savannah Riddle is bored. She is discontent. Fancy dresses, fine dining, charming young men paying her attention; none of it thrills her as it used to.

Her parents expect her to be an ornament in society, a well-behaved young lady who partakes only in approved causes (literary club, for example) and events (fetes and concerts, not protests or marches).

Instead, Savannah can’t stop reading the news: Spanish flu, race riots in East St. Louis and elsewhere, White women marching for the vote, anarchists planting bombs. With these headlines in her mind, she thinks her life of leisure and high society is meaningless.

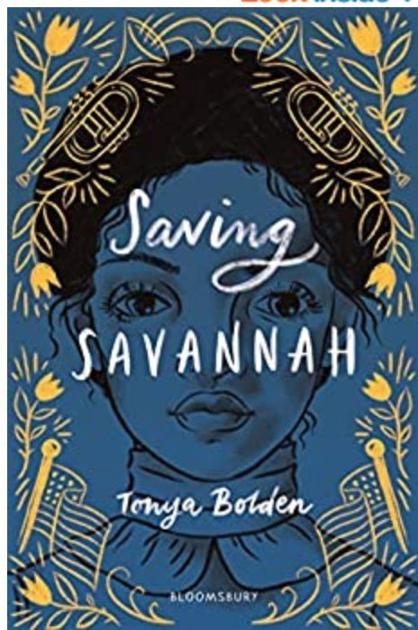

In this new historical novel, “Saving Savannah,” by Tonya Bolden, the reader will enjoy watching Savannah figure out what she cares about and how she can make a difference in the world.

That, in itself, drives the story along nicely. But the other element that engages the reader is the author’s detailed description of the Black upper class to which Savannah belongs.

The story is set in 1919 Washington, D.C., which, according to the author’s note, had, at the time, the largest population of affluent Black people in the country. We get to see so much of life 100 years ago. I haven’t felt this immersed in a setting in a long time.

In the first scene, at a big fete, Savannah wears a “bead-flecked emerald-green velvet dress with an ankle-length balloon hemline” and a top layer of chiffon.

Tables were groaning with so much fancy food: shrimp cocktail, oysters Rockefeller, salmon mousse, Lobster Thermidor.

The room had “snow-white damask tablecloths. Gilt-rimmed porcelain plates. Crimson napkins in standing fans. Sterling silver Tiffany Florentine flatware and gilt rim glassware.”

The partygoers danced the Castle Walk and two-step. Photoplays were all the rage.

In 1919, Jim Crow was alive and well, and even affluent Blacks had to follow the “color line.”

Still, as Bolden writes in her afterword, many portraits of Black lives under Jim Crow … “leave the impression that all black people — or most — were downtrodden, living lives of quiet desperation and deprivation. When black agency is brought into view, the focus is usually on lawsuits, marches, and boycotts. But there’s more to the story.”

Hence Bolden’s portrayal of the Black upper classes of Savannah’s set. It is a marvel!

Despite Savannah’s discontent, her Uncle Madison points out to her that the mere existence of this social group is a kind of social justice success.

“In the white press, how are we usually seen?” he asks Savannah.

“Sambo. Mammy. Criminals,” she answers.

“And dumb as a brick. Most white folks don’t want people like the Sandersons or the Riddles, for that matter, to exist. Let the world believe we’re all servants, sharecroppers, and such.”

In addition, many historical figures make an appearance in Bolden’s story, including W.E.B DuBois and Frederick Douglas.

But, I especially liked learning about those figures I’d not heard of, including Carter G. Woodson (the father of Black history).

Madam C.J. Walker I had known about, but readers learn about a second big-time, Black-owned beauty care business, Poro.

And then there is Nannie Helen Burroughs (a real person), who runs the Lincoln Heights School, a campus of five to six buildings outside the city whose motto is “We Specialize in the Wholly Impossible.”

Savannah, looking for a purpose, begins to help out there, and her world is immediately expanded. She meets other Black women who have come from far and wide seeking to make a difference in the world through their own efforts, with plans to run their own business, teach or otherwise help others.

“Saving Savannah” doesn’t present the Black population as a monolith. Bolden shows the differences within the Black community, simply as part of the setting.

First of all, there are clear class distinctions. The Riddles have other Black people come and clean their houses and do other chores, for example.

There is a poor section of D.C. where less-well-off Black people live. Savannah’s friend, Yolande, as well as Savannah’s parents are scandalized that Savannah would associate with people from that neighborhood, who Yolande refers to as “common folk.”

In addition, mention is made and judgment passed when someone’s skin is too dark or their manners are not polished enough. In addition, there are differing opinions about reform versus revolution, of working within the system or tearing the system (capitalism) down and building something better.

All in all, this book was a wonderful window into life in our nation’s capital 100 years ago. I’m sorry Savannah was unhappy with her plight, but I’m not sorry to know about this tale of success and affluence!

"story" - Google News

August 02, 2020 at 09:00PM

https://ift.tt/2DvIzoE

Deb Aronson | 'More to the story' | Books | news-gazette.com - Champaign/Urbana News-Gazette

"story" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2YrOfIK

https://ift.tt/2xwebYA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Deb Aronson | 'More to the story' | Books | news-gazette.com - Champaign/Urbana News-Gazette"

Post a Comment