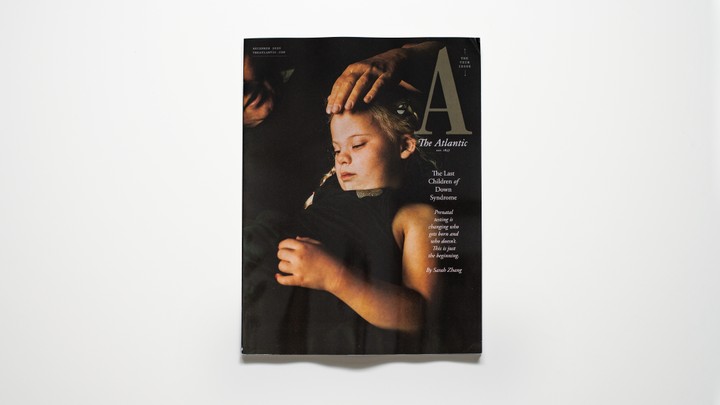

As prenatal testing becomes more widely available, parents face an increasing number of complex choices about their family’s future—choices that will only multiply as genetic testing advances to detect more and more fetal characteristics. For The Atlantic’s December cover story, staff writer Sarah Zhang reports on this rapidly evolving state of prenatal testing, the impact it is already having on the number of children born with special needs and vulnerabilities, and what it suggests about the broader future of genetic testing around the world. Her cover story, “The Last Children of Down Syndrome,” is out now.

Zhang’s reporting begins in Denmark, which in 2004 became one of the first countries in the world to offer prenatal Down syndrome screening to every pregnant woman, regardless of age or risk factors. Since universal screening was introduced, the number of babies born to parents who chose to continue a pregnancy after a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome has ranged from zero to 13 a year. In 2019, the most recent year for which data are available, there were seven. Why so few, and what might those numbers indicate about the future of humanity as genetic testing gets more sophisticated?

In interviews Zhang conducted with parents, doctors, scientists, and anthropologists, she heard again and again about the burden that universal prenatal screening puts on individuals, who must decide what to do after a prenatal diagnosis. Zhang writes: “There were fathers who agonized over the choice too, but mothers usually bore most of the burden. There is a feminist explanation (my body, my choice) and a less feminist one (family is still primarily the domain of women), but it’s true either way. And in making these decisions, many of the women seemed to anticipate the judgment they would face.”

Zhang continues: “The introduction of a choice reshapes the terrain on which we all stand. To opt out of testing is to become someone who chose to opt out. To test and end a pregnancy because of Down syndrome is to become someone who chose not to have a child with a disability. To test and continue the pregnancy after a Down syndrome diagnosis is to become someone who chose to have a child with a disability. Each choice puts you behind one demarcating line or another. There is no neutral ground, except perhaps in hoping that the test comes back negative and you never have to choose what’s next. What kind of choice is this, if what you hope is to not have to choose at all?”

As access to genetic testing continues to expand, and modern reproduction opens up more choices for parents in the process, these “choices” will get only more complicated. Scientists have also started trying to understand how to test for more common conditions that are influenced by hundreds or even thousands of genes: diabetes, heart disease, high cholesterol, cancer, and—much more controversially—mental illness and autism. We are in many ways only at the beginning of this science; what will its growing sophistication suggest about whose lives have value?

“The Last Children of Down Syndrome” is at The Atlantic today and on the cover of The Atlantic’s December issue. Stories from the December issue will continue to publish at The Atlantic throughout the month.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

"story" - Google News

November 18, 2020 at 06:15PM

https://ift.tt/3lM7YeI

The Atlantic's December issue press release - The Atlantic

"story" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2YrOfIK

https://ift.tt/2xwebYA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Atlantic's December issue press release - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment