The urban legend of the Candyman, a murderous ghost with a hook for a hand and old scores to settle, stems from a 1985 short story, “The Forbidden,” by the English horror writer and filmmaker Clive Barker. In that telling, a student doing field work in a poor housing estate unintentionally summons the vengeful spirit by interrogating locals about their old stories. The 1992 film adaptation, directed by Bernard Rose, moved the action from the slums of Liverpool to the Cabrini-Green housing project in Chicago and cast a Black actor, Tony Todd, as a velvet-voiced revenant in a floor-length shearling coat. And unlike Barker’s Candyman, who was given no name, race, or backstory, Todd’s Daniel Robitaille was the ghost of a specific man: the son of slaves who was murdered by a lynch mob after he fell in love with and impregnated a white woman whose portrait he’d been hired to paint.

Introducing racial violence and historical trauma into a slasher pic was an unusually bold move in 1992, which is part of why Rose’s Candyman became an important landmark in the cult horror canon, even though now it reads as the opposite of progressive in its racial and sexual politics. In 2021, though, it’s rare that a genre pic doesn’t attempt to allegorize contemporary social problems. Which leads us to the new, modern-day version of Candyman, directed by Nia DaCosta and cowritten by Da Costa and producers Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld. This Candyman positions itself as a “spiritual sequel” to the 1992 film (while politely ignoring the two subpar sequels, also starring Todd). It is also, in its way, an attempt on the filmmaker’s behalf to take the story of Daniel Robitaille, a descendant of slaves, back from its original white storytellers. Where the first Candyman centered around a white female protagonist and was directed by a white man, this version is not only directed and cowritten by a Black woman but also takes place in a largely Black world, with the white characters serving mostly as devices to drive the plot—and as fodder for some artfully filmed and spectacularly gory kills.

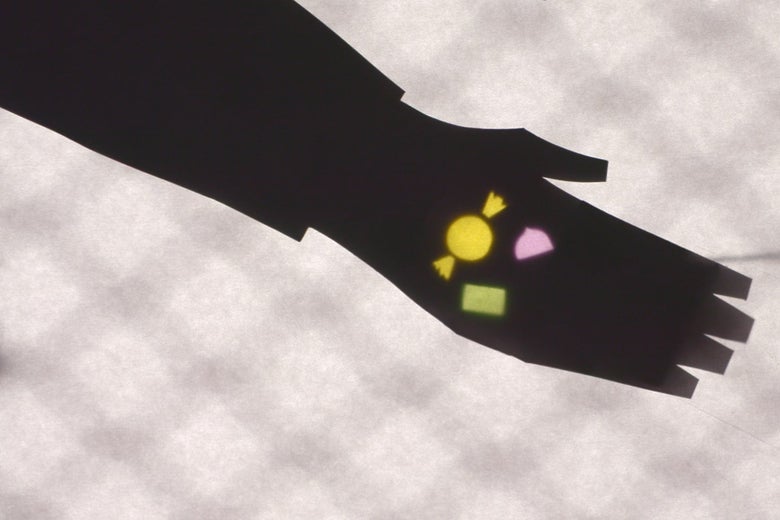

After an enigmatic prologue set in the Cabrini-Green houses in 1977, we jump to the present day, where painter Anthony (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) and his art-curator girlfriend Brianna (Teyonah Parris) live together in a luxury high-rise built on land that was formerly part of the projects. The fact that this ambitious young couple belongs to the same gentrifying class that Anthony’s work aims to critique is not lost on Brianna’s younger brother Troy (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett). Visiting their posh new apartment with his boyfriend, Troy lovingly skewers his sister and her boyfriend for their bougie lifestyle, before telling them a spooky story about a real-life tragedy that took place at the houses years before—essentially, he recaps the plot of the 1992 movie. This storytelling scene, like several more to come, makes use of a shadow-puppet technique that recalls the black-on-white, cut-paper silhouettes of the artist Kara Walker. Created by the Chicago-based design studio Manual Cinema, the delicate figures, operated by a hand whose shadow remains visible, are hauntingly expressive; stay through the end credits for a tour-de-force shadow-puppet play that condenses generations of suffering into a few painful vignettes.

The movie built around these puppetry scenes is equally stylish, if sometimes less substantial. DaCosta’s filmmaking makes frequent and deliberate reference to cinematic history, with many Kubrick-like compositions of oppressive symmetry, a few gnarly body-horror shots reminiscent of Cronenberg’s The Fly, and a climactic chase through a dark tunnel that recalls the finale of The Silence of the Lambs. There is a clever and sometimes stunning deployment of mirrors as the surfaces through which both the audience and characters are able to access an alternate reality, or maybe just look past the artifices of daily life to see the gruesome reality that was always there. When he looks in a mirror—the place where, according to legend, the Candyman will appear if you say his name five times—Anthony sometimes sees the hook-handed figure looking back at him, played once again by the still-frightening, even more poignant Todd. Several murders are seen only in mirrored reflections, most memorably a bloodbath in a public bathroom that’s glimpsed in the tiny round mirror of a teenage girl’s makeup compact.

The first hour of Candyman does a bang-up job of mixing such audience-teasing popcorn thrills with trenchant, if sometimes too flatly stated, social critique. But by the last half-hour, there are so many themes, plotlines, and flashbacks in play that the movie’s message becomes muddled, and the forward momentum slows. Anthony grows obsessed with the Candyman legend, visits the remaining structures on the Cabrini-Green site, and meets a middle-aged laundromat operator named Burke (Colman Domingo) with chilling stories to tell. Anthony also, it’s implied, makes a kind of Faustian bargain with whatever evil force the Candyman represents: When he creates and exhibits an art piece that encourages viewers to summon the mirror-dwelling killer, his place in the art world almost immediately begins to rise. Brianna gets her own tragic backstory, communicated in one too-brief flashback, and Vanessa Williams, reprising her role from the 1992 movie, makes a single-scene appearance as Anthony’s troubled mother.

By the time Brianna, a disturbingly transformed Anthony, an ever more jittery Burke, and the ghostly Candyman have their final confrontation at an abandoned church, it is no longer clear who stands for what or what anyone’s motivations are. The Candyman, formerly an embodiment of the historical suffering of Black people at the hands of white supremacists, suddenly appears to be a standard-issue slasher villain chasing down a “final girl,” who is herself Black, while Abdul-Mateen’s Anthony is uneasily suspended between zombie-like victimhood and righteous moral agency. Todd, Parris, Domingo, and Abdul-Mateen are all gifted and charismatic performers that, in the earlier scenes, bring complex shadings to their neither all-good nor all-bad characters. But by the time the movie reaches its extended, free-form slash-a-thon finale, even its compact 90-minute running time starts to feel a little slack.

DaCosta will next direct the superhero installment The Marvels, which also co-stars Teyonah Parris. Candyman—only DaCosta’s second movie, after the taut 2018 social-realist indie Little Woods—sometimes fails to trust its audience’s intelligence enough to let us make our own connections between the atrocities of the past and the barely suppressed violence of the present. But it does amply display that this young filmmaker has style and promise to burn.

"story" - Google News

August 27, 2021 at 04:36AM

https://ift.tt/3BdFWQM

Candyman (2021) review: A spiritual sequel to the horror classic. - Slate

"story" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2YrOfIK

https://ift.tt/2xwebYA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Candyman (2021) review: A spiritual sequel to the horror classic. - Slate"

Post a Comment