Their story—the one I was writing, and the one I wasn’t—had to have a happy ending. There was no other way. Juan Carlos Perla, a man of faith and a man of rules, insisted.

Of course, it wasn’t that simple. His story, after all, is something of a parable about the crushing machinery of the Trump era’s immigration system. And we weren’t even at the ending to know what it might look like. Not that I’d say any of that to Juan Carlos—of all the many times we’d talked, this was a phone call full of good news.

It was early March, two days before he and his wife, Aracely, and their three young boys would be allowed to enter the United States. From the small room in a Tijuana church where the Salvadoran family had been living for the past nine months, Juan Carlos, 38 years old, was asking me what it feels like to fly.

“Now that I’m really nervous about. We’ve never been on an airplane before. Is it kind of like those rides at the county fair?” he asked. “You know, like the big ship one that rocks side to side? Because I can handle that.” His kids—Jeremías, 9; Carlos, 6; and Mateo, 3—were excited to get on a plane. His wife hadn’t said much about it. But as Juan Carlos admitted to me, he tends “to be a bit more of a nervous person than my wife, and right now I’m pretty nervous about all of this…I hope it all goes well. I know it will go well.”

There were other things to worry about first: All five of them had to test negative for COVID-19, and none of them had been tested before. “Do they touch the back of your throat when they do the test? Does it hurt more when they put the stick up your nose?” Juan Carlos asked me, his mind racing on the WhatsApp call. They also had to isolate for a night in a Mexican government–run shelter, get processed by US Border Patrol, test negative again for the coronavirus, and quarantine in a San Diego hotel. And then they could fly.

At that point, the Perlas, with just two suitcases in hand, would be allowed to enter the United States and settle in Oregon—at least temporarily. The hope was that in the US, the family would have a better chance to make their case for asylum. They’d spent the last two long, painful years remotely trying to make that case, to little effect, and moving from one limbo to the next. “It was two very heavy years,” Juan Carlos told me, “full of tears, persecution, pain, hunger, suffering, anguish, and racism against us from Mexico and the US.”

Throughout most of that time, we had talked on and off, and I had grown to expect a certain openness from Juan Carlos when things were tough, as well as his lighthearted jokes when he was feeling more optimistic. I had met the Perlas in Tijuana in early 2019, the day before they first presented themselves for asylum at the San Ysidro port of entry in San Diego. But instead of navigating the daunting and complicated US immigration system from inside the US, as the Perlas had expected when they left home, a Trump-era policy known as “Remain in Mexico” kept them south of the border while their asylum case moved through the courts north of it. More than 70,000 people got stuck in the program. When President Joe Biden took office, he reversed course, suspending Remain in Mexico. Then he declared that the roughly 25,000 people who still had open cases pending under this policy would be slowly allowed into the US. More than 40,000 people had already missed out; their cases were closed. (And so far they seem to be out of luck. Biden hasn’t said if their cases will get a second chance.)

The new administration started with the most vulnerable and with those who’d been waiting the longest, like the Perlas. “I can’t really find the words to describe how it feels right now,” Juan Carlos told me that night in the Tijuana church. [Listen in Spanish 🔈]

While the Biden administration has so far been overwhelmed by a seemingly unceasing need at the border, and preoccupied with reversing other immigration cruelties left by President Trump, Remain in Mexico is no longer the most immediate crisis. But it will nevertheless go down as one of the most significant policies of the Trump era, one that was monumental in shifting how the US handles asylum. And its horrors, and those of the administration’s immigration regime writ large, will not be neatly wrapped up anytime soon. Remain in Mexico determined the fates of tens of thousands of men, women, children, and families like the Perlas. So while the program has officially ended, with the Biden administration formally shutting it down this week, we’re still far from its conclusion.

“We only know a fraction of the harm that the policy enacted on people because we only know the stories that were reported by journalists and that we were able to speak to,” said Robyn Barnard, the senior advocacy counsel with Human Rights First. The organization reported more than 800 cases of kidnapping, rape, assault, and torture for asylum seekers forced to wait in Mexican border cities in just the first year of the policy.

“We’re still in the thick of getting people out of harm’s way in Mexico,” Barnard told me recently. “People who want us to create these barriers and walls to asylum seekers miss the point that people come here because they still see the United States as a beacon of hope and safety.”

More than 70,000 asylum seekers enrolled in Remain in Mexico

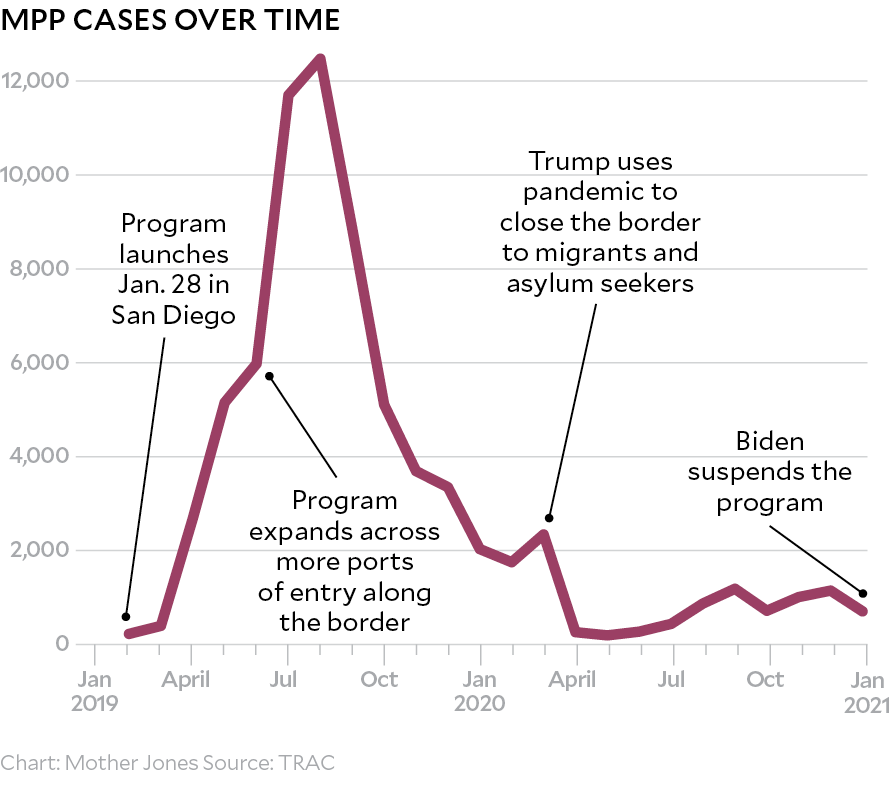

In total, more than 70,000 individuals were placed in the program, with nearly 30,000 people added in just three months in the summer of 2019 as MPP expanded to more ports of entry. The top five nationalities of asylum seekers in MPP were, in descending order, Honduras, Guatemala, Cuba, El Salvador, and Ecuador.

“We wanted everything to be done legally. We didn’t want to break any laws,” Juan Carlos told me late last year. But, he said, “if I had known back then what I know now, we wouldn’t have waited to present ourselves at the port of entry. We would’ve just tried to cross illegally.”

“We thought we were doing the right thing,” he added.

Their saga starts back in October 2018. Juan Carlos was reluctant to share too many details about how bad things were for them in his hometown because “you never know where these people are and I don’t know if they’ll read this in El Salvador.” He said he felt comfortable sharing only that he had been the victim of extortion in his bakery business and that his life and the lives of his family had been threatened.

“We left in the middle of the night with $500 in my pocket and scared,” Juan Carlos told me.

When they made it to the Guatemala–Mexico border, they met a person who assured them he could help them navigate the river. Once it was time to cross, the smuggler “threatened me and told me to give him all my money,” Juan Carlos explained. “I didn’t have another option but to give it to him.”

They made it into Tapachula, the first Mexican city most migrants pass through on their way north, and there the family caught up with a large migrant caravan passing through. “It ended up being a blessing because we were able to get some support with food and milk and diapers for the kids,” Juan Carlos said. Mateo, the youngest, was only 6 months old.

When the caravan left, Juan Carlos thought it’d be best for his family to do things by the book. They decided to stay behind and wait for humanitarian visas from the Mexican government that would allow them to legally travel through the country.

The following two-month wait was among the toughest stretches of their whole ordeal. At Trump’s request, Mexican government officials had increased enforcement efforts along the country’s southern border to try to stop or slow down migrants and asylum seekers headed for the United States, which in turn created an environment of local resistance and discrimination toward migrants. Juan Carlos was able to work as a security guard for a few nights, hoping to make enough to feed his family for a week, but he stopped because he never got paid. They scrambled to get by, sometimes asking passersby for change. “People there called us names, they told my oldest kids that they would never give money to people like them and that they should go back to their country,” Juan Carlos told me. “My oldest son was so sad and after that he stopped begging for money.”

When the Mexican government finally issued their visas, they took buses, hitched rides, and walked, until they made it to Tijuana in late January 2019.

Once at the border, Juan Carlos hoped he could quickly make his asylum case to border officials. But for about a year, US Customs and Border Protection officials had been telling asylum seekers that there wasn’t enough space at the ports of entry or enough agents to take them in for processing, so they had to wait south of the border. Trump, meanwhile, was saying the country was “full.”

Waitlists started informally at first, as nonprofits sought to give families a chance to leave the port of entry and go to a shelter for a warm meal and a shower without losing their place in line. But as time went on and the backlog grew, particularly in bigger cities like Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexican agencies took charge of the waitlists. And while US officials never took formal responsibility of these lists, they did call out how many cases they’d admit every day: sometimes 10, sometimes 30, sometimes none at all.

After a few days in Tijuana, the Perlas were finally able to get on a waitlist. There were 2,000 numbers ahead of theirs. Juan Carlos was shocked; they had no connections in the city, leaving him scrambling to find a shelter that would take them as a family.

He’d known that requesting asylum wouldn’t be easy or simple, but he never anticipated he’d sit on a list, languishing for two months before he could even speak with US officials. And even then, he was unable to make his case from inside the US. While the Perlas were waiting for their turn in Tijuana, the Trump administration was launching an asylum deterrent program that would flip the whole system on its head.

The Migrant Protection Protocols, the formal name for Remain in Mexico, was an unprecedented program whereby non-Mexican migrants seeking asylum in the United States were detained for a few days at the border only to be released back into Mexico with a piece of paper that had a date and time for a court appearance, condemning already vulnerable people to the streets of a foreign country with little to no support. Many people placed in MPP spoke indigenous languages, putting them even more at risk of abuse in Mexican border cities.

When I met Juan Carlos at the end of February 2019, he was standing in a red tracksuit jacket and jeans with his family in the shadow of an overpass in Tijuana, next to giant block letters that spelled out “Mexico.” He was visibly anxious, pacing back and forth, often touching his clean shaven face. Around him, hundreds of migrants huddled, waiting to hear how many numbers would be called that day. Just as he had been doing for weeks, Juan Carlos stood in the crowd clenching a duffle bag in one hand and a little piece of paper with a four-digit number in the other.

I overheard him tell his wife, “We didn’t make it today…we are seven numbers short.”

After we started talking, he told me, “Hopefully it’ll be our turn tomorrow.” Two of his young sons looked up at him and smiled. Carlos, just 4 years old, wore a beanie with fuzzy koala ears; he was carrying a blanket because, as he told me, it got really cold in Tijuana. Aracely, nearly a foot shorter than her husband, with her dark hair tied tight into a ponytail, rocked Mateo from side to side to keep the infant from crying.

The next morning, Juan Carlos, duffle bag again in hand, was back at the port of entry with his family when their number was finally called. Juan Carlos put all his trust in God, anxious to finally be in the hands of US authorities, even if it meant he and his family would be detained. “We just can’t be in Tijuana any longer,” he told me over a WhatsApp call.

I didn’t hear from him for four days. When he finally reached out, it was to let me know that they had just been released by US border authorities. “We’re back in Tijuana,” he said, sounding defeated.

At the port of entry, Juan Carlos had been separated from his wife and children. “They put us in the hieleras”—Border Patrol holding cells infamous for their cold temperatures—“and they didn’t tell us anything.” On his second day in the detention cell, a Spanish-speaking officer interviewed him for just about 20 minutes.

Another day went by. Juan Carlos didn’t know what was going on with his wife and kids. By day three, the family was reunited—only to be walked right back into Tijuana with a document declaring that their first US court date was in April. All five had officially been placed in the Remain in Mexico program. They had no other instructions and no idea what to expect.

Juan Carlos was on the verge of tears when we spoke that day. “If that judge doesn’t give us asylum, we could be deported back to El Salvador right then,” he said. “And that would be a death sentence.”

In early April 2019, ahead of their first court date in San Diego, I spoke again with Juan Carlos. They had been staying at a migrant shelter in Tijuana, and he told me how the other families there in MPP left at dawn for their own court dates and came back at dusk—exhausted, stressed, and with no answers about their futures.

“I didn’t want to put my kids through the back and forth,” he told me, alluding to the fact that in many cases, asylum seekers had been handcuffed when transported to court by Immigration and Customs Enforcement and agency contractors. “I didn’t want them to see that, and also didn’t want them to get sick with a cold or anything.” More importantly, without any legal representation, he feared a judge could deny them asylum. Juan Carlos knew this would be a huge challenge; he had been asking around for any free legal assistance in Tijuana, without any luck.

“So, Mexico might be our only option right now,” he said, to my surprise. I asked him if he was thinking of dropping his asylum case, and he explained that the three days in border holding cells were traumatizing. That, along with the vast uncertainty of what it meant to be in MPP, made him think of giving up. This was one of the program’s goals: to strip any hope from asylum seekers so they would drop their asylum claims. Through Remain in Mexico, Trump and his senior policy adviser Stephen Miller plainly exhausted and obstructed people from seeking refuge in the United States.

“We’ve gotten the idea of going to the United States out of our minds for now,” Juan Carlos said. “The laws are all messed up in the United States, and who knows when they’ll change, so I’d rather fight for my kids here.”

With help from the organization Families Belong Together, the Perlas were able to relocate to a small town called Las Palmas, about an hour from Tijuana. Juan Carlos felt a bit safer there. “We have faith that God always puts people with good hearts in our path,” he told me then. He got a job at a meat shop and his wife worked part time as a house cleaner for their landlord. His boss donated food to the family and a neighbor gave the kids some used clothes. The two older boys were happy that the landlord had left a TV in the house and a friend gave them a DVD player. It had been more than six months since they had left home, and the youngest boy was about to turn a year old.

Then, in early April, as they were carving out a life there, a federal judge temporarily blocked Remain in Mexico. Juan Carlos saw it as a hopeful sign they might get into the US after all; he called the number on the paperwork he got back at the port of entry and received another US court date, this time in July.

By then, the policy had resumed.

When it was time for the family to try again in court, they gathered their paperwork and left Las Palmas. They returned to the San Ysidro port of entry to be processed and then taken to court in San Diego; they were asked to show up at 9 a.m. for their 1 p.m. court hearing. They were grateful for an afternoon hearing because the US government had been making some people show up at the border at 3 or 4 a.m.

“The whole experience was so nerve wracking,” Juan Carlos told me. US border agents took a group of asylum seekers by bus, escorted by guards. Once in front of a judge, the adults in the group were given headphones so they could listen to a Spanish interpreter. Juan Carlos said they were asked, as a group, if they had lawyers. “We said no and the judge asked if we wanted more time to find lawyers and we said yes. That was it,” he told me. That evening, the bus drove the group back to the border.

The disappointment turned to shock when the Perlas returned to their small rental in Las Palmas. “We came back to find that the [landlord] had packed up our things and given them away so we had nowhere to go,” Juan Carlos said. “I had even fixed up the place, but she treated us like invaders, and my kids are the ones who paid the consequences.”

They headed back to Tijuana.

There, a friend told him about an empty trailer where they could stay—essentially an abandoned school bus without seats. “It was really old and full of ants, mosquitoes, and even rats. My middle son ended up covered in bug bites at one point.” They didn’t stay long.

It was almost impossible to get a lawyer from Mexico

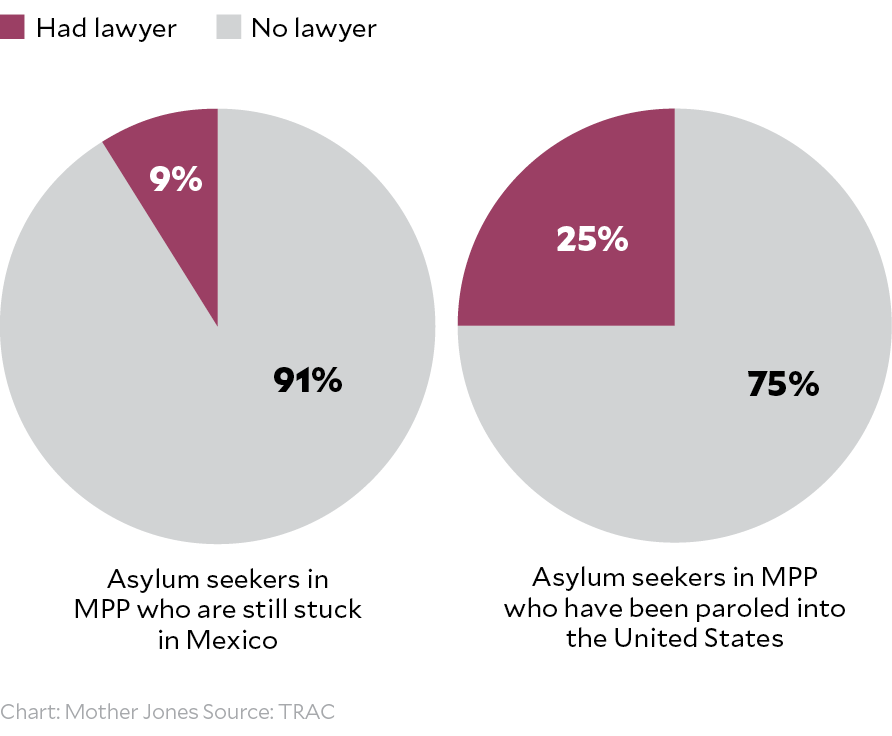

MPP was designed for failure. Asylum outcomes rely heavily on access to attorneys, and, as the story of the Perla family shows, MPP made finding an immigration attorney nearly impossible while stuck in Mexico. As a result, migrants in the program were forced to navigate a confusing, messy, and foreign legal system all by themselves.

The family was in and out of shelters in Tijuana for the rest of 2019. Every day was a struggle. “Sometimes I wanted to throw in the towel, seeing what my kids were going through made me feel guilty,” Aracely told me recently. [Listen in Spanish 🔈] The instability is what got to her the most. All three of their boys had celebrated at least one birthday in Mexico. The two older boys had missed out on a lot of school. And the youngest had now spent most of his life in Mexico. She tried her best to hide how dire the situation was, but it was becoming harder. Especially when Jeremías noticed Aracely crying. She told me he consoled her with hugs and “sweet words” that helped more than he’ll ever know.

I started to hear a change in Juan Carlos’ voice. Some days he was his typical upbeat self, grateful for the “good people” who had helped them—like the kind man who bought the family lunch after he overheard his kids say they were hungry at a plaza. Other days he sounded worn down and depleted, angry at the “not so good people,” the people who called them animals when they were living on the streets.

“We tried to go on walks so [the kids] could see the good parts around us and try to forget about everything else for a moment,” Aracely told me. “They really enjoyed those moments, and more importantly we were always together. We’ve always been like that, all five of us are linked—we are all one.”

The family returned to the port of entry five more times over the course of a year; each time they were processed at the border at dawn, taken to court in San Diego, and returned to Tijuana at dusk. “Not much” would happen in court each time, Juan Carlos said, and the family still didn’t have a lawyer. He had tried calling the numbers on the one-page document provided by the courts, which listed a handful of San Diego–based organizations that might provide pro-bono attorneys. But his calls from Mexico didn’t go through. He tried calling attorneys in the US. They either told him they couldn’t help people in Mexico or were charging more than he could afford. Like the majority of asylum seekers going through MPP, the Perlas were lost in the tornado that is the US immigration court system, not speaking the language, and unaware of how the foreign legal system worked.

“It was a travesty of justice,” said Jaya Ramji-Nogales, author of The End of Asylum: The Trump Administration’s War on Asylum and What Congress and the Biden Administration Can Do About It. “There was just no due process there.”

I had first seen inside the tornado in March 2019, when I sat in on one of the initial MPP cases heard in immigration court in San Diego. The whole operation was a mess. Lawyers representing asylum seekers told me the process was full of conflicting information and confusing court dates. And this was for people who had attorneys. About a year later, in January 2020, I again sat in on about a dozen MPP hearings; it was still chaos, if a slightly more organized version. I saw jam-packed waiting rooms with dazed-looking families who had been awake for too many hours and were escorted in and out of courtrooms without lawyers. Adults who spoke indigenous languages and only a bit of Spanish were given Spanish translations they didn’t seem to fully understand; judges held group hearings, barely looking up at the faces of those whose cases they were moving along. It was designed to fail.

Almost no one in MPP was granted asylum

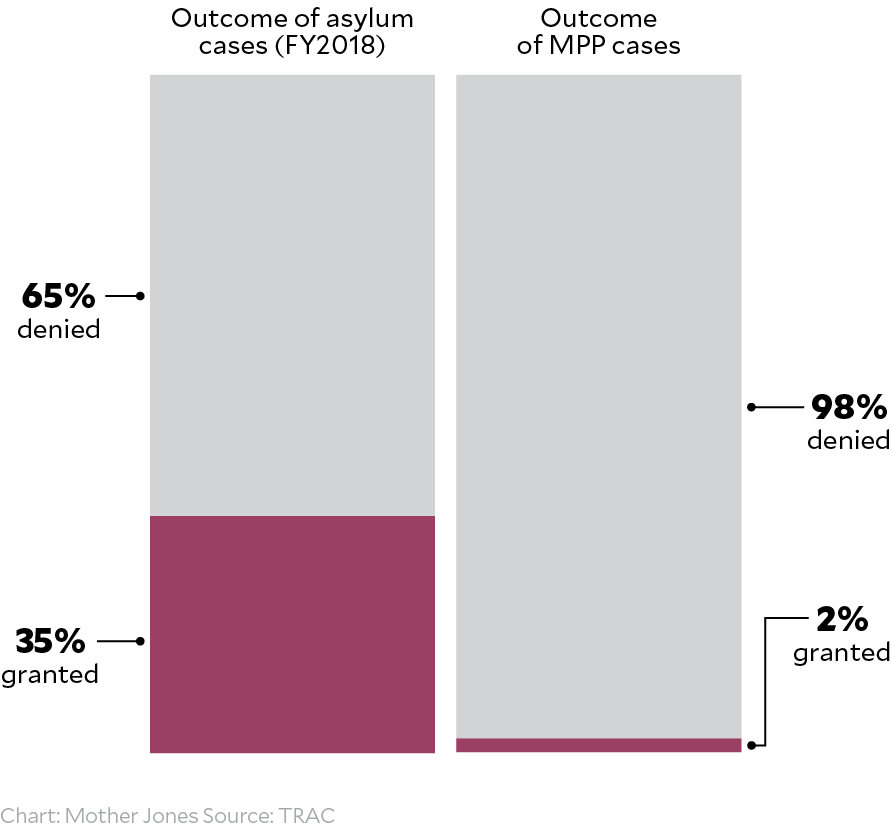

Asylum was not easy to obtain before Remain in Mexico, but the Trump administration used MPP to make asylum nearly impossible. In 2018, the last fiscal year without MPP, 42,269 cases were closed, with more than 30 percent of those receiving asylum. For the 41,732 MPP cases that were closed, less than 2 percent received asylum.

“The due process component of it is really, really problematic,” said Ramji-Nogales, who is also a professor at Temple University’s Beasley School of Law. She told me about the thousands of people with court dates near the Brownsville–Matamoros border in Texas who didn’t even get see a judge in person. Instead, the Trump administration set up a sprawling complex of tents where groups of people in MPP would see a judge briefly via video call.

The Perlas did see a judge in person, but over their six court appearances, they were never able to explain their case to the judge.

Finally, in early 2020, just before the world was overturned by the coronavirus, everything changed for the Perlas. They reconnected with, as Juan Carlos put it, their “angel.”

Maria Lourdes “Lulu” Arias Trujillo is a migrant aid worker who had first met the Perlas in 2019 when she’d helped the family move to Las Palmas. This time, Lulu and other workers with the US nonprofit One Story at a Time supported the family with essential items and helped Juan Carlos set up a fruit stand. “I call her our angel, because she truly is an angel sent from God to help us,” Juan Carlos told me.

“I connected with their heart and their integrity,” Lulu told me recently in an email. “When I met them, it was Aracely who touched my heart because she was honest, Juan Carlos was hard working, and their children were still kids with innocent souls and pure hearts…They were looking for a better life for their children and they had gone through a lot, so for me, that was very brave and they inspired me to help them.”

Linda Carroll, founder of One Story at a Time, says she “was so blown away with them.” “Aracely was taking some English classes, Juan was off working trying to make ends meet, and then those little boys were so cared for that I just thought this family belongs in America, we need them in America as much as they need us,” she told me. Carroll wrote about the Perlas in her newsletter, asking for donations, and raised enough to hire them a lawyer. She also found a sponsor for the family in the United States: Nancy Kyle, a retired researcher at Oregon State University living in Corvallis, Oregon.

With a lawyer and a sponsor, Juan Carlos felt like they finally had a fair shot. But the family’s final court hearing was supposed to be in March 2020—just as the pandemic was taking hold. He said their hearing was postponed five times over the next eight months, and he was finding it harder to remain positive. [Listen in Spanish 🔈]

Over this period, Trump essentially closed the border to all asylum seekers—for those already in MPP, since court cases weren’t moving forward, and for everyone else, through the invocation of Title 42, a public health rule Trump used to turn back arriving migrants and asylum seekers alike without any chance to petition for protection. As a result, migrants began to further crowd into border cities like Tijuana, and Juan Carlos worried that things would get even more grim.

As the pandemic worsened, so did economic opportunities for most people stuck in Tijuana. Juan Carlos told me that the vegetable stand wasn’t enough to get by anymore. “I’m picking up trash now,” he said with a bit of a shake in his voice. “I go from dumpster to dumpster looking through the garbage to see what I can find that then I could clean up or fix so I could sell them. I use that money to feed my family.” Sometimes his oldest son would join him.

It had been almost a year since Lulu had connected them with a lawyer and a sponsor, and nothing had changed. It’d been two years since they arrived at the border. Juan Carlos was losing hope again.

Then he heard the news that “the new president of the United States” had a plan for “people like us.” [Listen in Spanish 🔈]

On February 12, 2021, the Biden administration announced it would implement a system for people with active MPP cases to be able to enter and stay in the United States while their court cases were heard. They’d have to register online, get tested for COVID-19, and isolate ahead of their intake. The president promised to require check-ins with ICE officials at their final destination rather than send these asylum seekers to detention; the administration was also considering the use of ankle monitors.

Of the roughly 25,000 people who had pending cases at the time, more than 11,300 have entered the United States to continue asylum claims from here, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the Department of Homeland Security. They’ve transferred their cases to cities across the United States and, according to data from TRAC at Syracuse University, most MPP cases are being transferred to Miami, Orlando, Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio.

But about another 40,000 people had had their cases closed by the time Biden took office. The Trump administration simply and cruelly took away their legal right to properly seek refuge in the United States, their opportunity at a fair shot—and it’s unclear if they’ll ever get another one. “The enormity of the human cost is just heartbreaking,” Ramji-Nogales said. “Just so much cruelty to people, and there has to be a better way…in the end this comes down to politics, what kind of nation we live in.”

The future of MPP is unclear. The program was officially shuttered this week, but the legal case challenging MPP is headed to the Supreme Court—though one thing the Biden administration could do is withdraw its appeal for fear of “a really bad decision,” Ramji-Nogales explains, setting a dangerous legal precedent that would validate MPP and allow the US government to easily replicate its cruelties in the future.

A majority of immigration judges deny more than 70 percent of cases

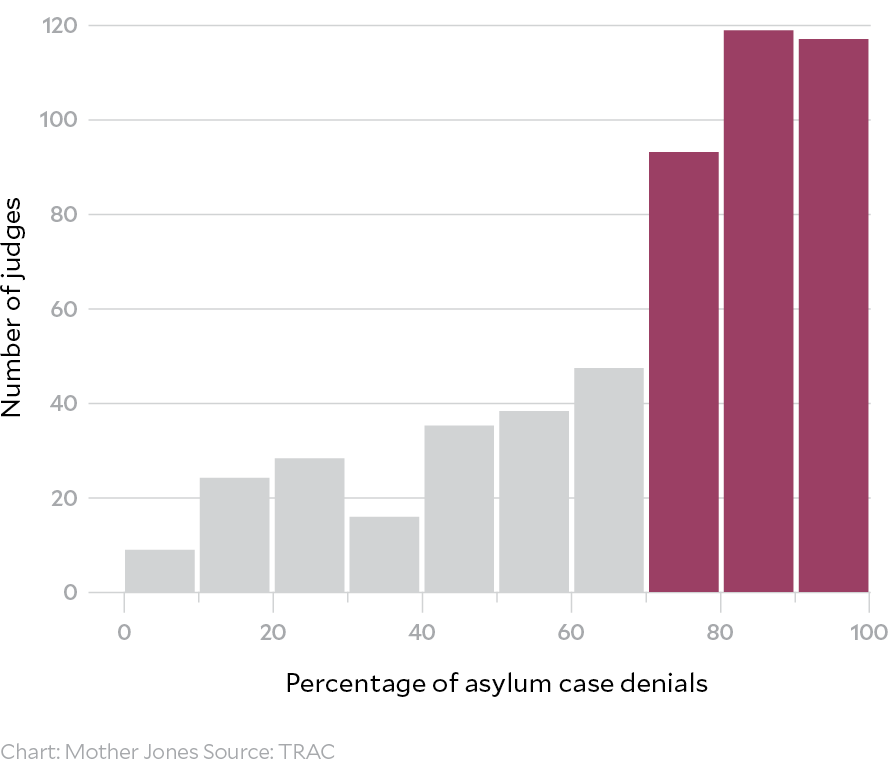

Immigration judges are supposed to decide asylum cases impartially but massive disparities exist between judges and between immigration courts, regardless of the merits of individual cases. Between 2015 and 2020, most judges denied over 70 percent of asylum cases they heard. One judge in Houston denied 100 percent of them. Others in Georgia, Louisiana, and North Carolina denied more than 99 percent of the asylum cases they heard.

Barnard, from Human Rights First, also told me she worries about Remain in Mexico being used as a way to push the idea that asylum seekers shouldn’t enter the United States “even though that is their legally entrenched right…that’s my biggest concern.”

“We’re going to look back and see this as a steppingstone to worse externalization of US asylum processing.”

Even though he can handle the kinds of rides he once rode at town fairs, Juan Carlos had a terrible time on the plane. “I just took deep breaths and pushed that button above my seat that pushed air out on my head,” Juan Carlos told me in March, a day after their flight from San Diego to Portland. “My wife and kids were loving it, looking out the window of the plane, laughing and taking videos and photos.”

Once they landed, they had no idea where to get their luggage. They turned to a few people, asking “Spanish?” with no luck. Finally someone showed them the way to baggage claim, and when they stepped out of the terminal they were greeted by a volunteer who took them to their new home in Corvallis, a small city 85 miles south of Portland.

Nancy Kyle, their sponsor, had been preparing for their arrival. She’d never done anything like this before. “I just thought, I have to do something, I can’t not do this…I can’t fix the immigration issue, but I can help this one family,” she told me. She had talked with the Perlas’ lawyer, and with other members of her church and a wider immigrant support network, the Interfaith Immigrant Support Team, about what sponsoring the Perlas would entail. She set up living quarters for them at the church, where they would have their own room and kitchen access, since the church was sitting unused during the pandemic.

“You wouldn’t believe these wonderful people—they’re treating us like royalty,” Juan Carlos said the day after they got to Corvallis. “They were so emotional when they welcomed us. They were crying, they brought us food, they had this little place set up for us. They all were speaking English, but we figured things out.”

Juan Carlos told me that all five of them slept like babies their first night there, the first time after more than two years of uncertainty, two years of constantly living in survival mode, that they could finally relax.

By their second week, the kids had been enrolled in virtual school, and Juan Carlos had started volunteering at the local food bank. “The rules say I can’t work until we get a work permit, and we’re going to continue to follow the rules, but I need to be doing something,” he told me. He’s also been practicing his English and told me that a few folks in Corvallis have started calling him “JC.” He liked the sound of that in English: “Jay-cee, sounds good, no?”

Despite languishing in the Trump administration’s MPP border hell for some 130 weeks, the Perlas consider themselves lucky.

“I already know that once we get on our feet, and I can take care of my family again, then I’m going to make sure to come back to this group and help another family like us in the future,” Juan Carlos told me in April, explaining how Kyle and her congregation have all pitched in to get them their own apartment for a year. “It’s incredible to see how much they’ve done for us.”

But in our weekly conversations from Oregon, it was also hard not to contemplate everything else, all that had happened, all that was still ahead.

Carlos, their middle child, was only 4 years old, wearing that koala beanie, when I first met the family in Tijuana. He recently sent me a voice memo: “I’m so much happier now because I go to school, and I have new classes and a computer so I can study,” Carlos, now 6, explained. “Here, we have a house where we feel better and where we will stay every day.” [Listen in Spanish 🔈]

Jeremías, now 9, also sent me some voice memos reflecting on their journey. [Listen in Spanish 🔈] “In Mexico, I would go pick through trash with my dad. We’d leave early in the morning to look through the garbage for stuff to sell and sometimes had to look through trash to find food,” he said. “My dad worked so hard so we could get to this place, and now we’re in the United States and I feel happy to be here with my family. I feel so grateful for the good people God put in our path and so happy that I am studying now because my dream is to become a doctor one day so I can save many lives.”

Maybe this is what Juan Carlos meant when he told me he was glad I’d be able to tell their “full story with a happy ending.”

I was reluctant to remind him this ending isn’t an ending at all. Oregon is just a new chapter—a huge but ultimately temporary reprieve. Shortly after they arrived, the Perlas’ lawyer checked in with the local ICE office, officially transferring their asylum case to a nearby US immigration court, likely in Portland. But their case could still take months, or even years, to finalize. And if a judge does not grant them refuge here, they’ll have to try and find other legal avenues to stay, and the whole process could still end in deportation back to El Salvador. Their futures—the possibility of Jeremías becoming a doctor, of Juan Carlos paying it forward—overwhelmingly depend on what one person decides about their story. Data shows how much asylum claim outcomes vary by judge; the majority of immigration judges deny more than 75 percent of all asylum claims they see, and 10 percent of all immigration judges deny over 95 percent.

But in one of our last calls this spring, Juan Carlos circled back yet again to this notion of happy endings: “It really is a happy ending for us. We’re here and we’re safe now and it’s thanks to good people we met along the way and thanks to the new president that let us in,” he told me, his voice light and warm. “A real happy ending.”

Just a few days later, Juan Carlos sent me a photo of the five of them. They’re straddling a pack of bikes, wearing helmets and gray and blue pullovers, giving off some serious Pacific Northwest vibes. “It’s so beautiful here,” Aracely told me when Juan Carlos handed her the phone to talk to me. “The weather is just a little chilly but in a nice way.”

Juan Carlos Perla with Aracely and their three boys—Jeremías, Carlos, and Mateo—in Corvallis, Oregon.

Courtesy of the Perla family

Story: Fernanda Echavarri

Data: Austin Kocher/TRAC

Data visualizations editor: Sinduja Rangarajan

Illustrator: Hokyoung Kim

Art directors: Adam Vieyra and Michael Johnson

Web developer: Julia Smith

Editor: Amanda Silverman

Fact-checkers: Isabela Dias and Piper McDaniel

"diary" - Google News

June 04, 2021 at 04:32PM

https://ift.tt/3uLX5xr

One Family's Escape From Trump's Border Hell: A 130-Week Diary – Mother Jones - Mother Jones

"diary" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VTijey

https://ift.tt/2xwebYA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "One Family's Escape From Trump's Border Hell: A 130-Week Diary – Mother Jones - Mother Jones"

Post a Comment