A myth that circulated throughout my MFA program was that of a respected professor holding up a student’s paper, slamming it down on his desk, and declaring, “This is just a fucking story.” To a group of twentysomethings trying to be artists, writing “just a story” was an egregious insult. Narrative for narrative’s sake was a waste of paper and potential. Art should do more.

Years after leaving academia, I still preferred a more substantive narrative, the kind my professors insisted upon me. When I first met my partner, Jed, in 2018, he tried to get me into anime by showing me programs that fit that bill. That spring, for example, we watched Penguindrum together, a surreal exploration of how isolation, abuse, and terrorism impact children. With family border separations dominating the news cycle, the show hit hard; I never knew anime, a genre I mostly associated with kiddy programs like Pokémon and Sailor Moon, could be so contemplative, so searing, so relevant. But when Jed started pushing me to watch JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure later that year, I pushed right back. Everything I knew about the show—the campy dialogue, the classic rock references, the legions of preposterously burly men with ludicrous superpowers—felt silly and insubstantial. JoJo seemed fun, sure, but not for me. I preferred something more meaningful.

Two years passed, however, and I began to find dwindling comfort in haughtier works. Between the pandemic, ongoing climate crisis, and widespread political chaos, high-brow art felt like insufficient solace against an unstable world. In early 2020—overwhelmed by hot-takes and think pieces regarding our present circumstances—I thought of Joan Didion’s most famous quote: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” In its full context, she’s actually speaking about the danger of viewing life through a narrative lens, evident in the modern coalescence of entertainment and reality. We depend on comedians for political commentary and power through true crime podcasts like we’re reading pulpy mystery novels.The most popular docu-series are all focused on death, cults, and pyramid schemes.

Not all of today’s entertainment is sinister. Much of fiction now comes with the expectation that it will offer concomitant social commentary, which is inarguably positive, even if that commentary is sometimes hamfisted and clumsy. Demanding more from our content—more accountability, more responsibility, more representation—creates more empathetic, informative narratives. I read about 10 pieces a week about what X show says about Y cultural phenomena, essays that are well-written and highlight issues worthy of our attention. But at the same time, I’ve become increasingly burnt out by this imposition that everything must mean something to matter, that there is no room for stories that help us escape the present rather than viewing it from a metaphorical vantage point.

In July 2020, that sense of burnout at its peak, I asked Jed, almost unconsciously, “What’s that show you’re always trying to get me to watch, where the men wear skin-tight jumpsuits and everything’s named after a classic rock song?” And so my journey began.

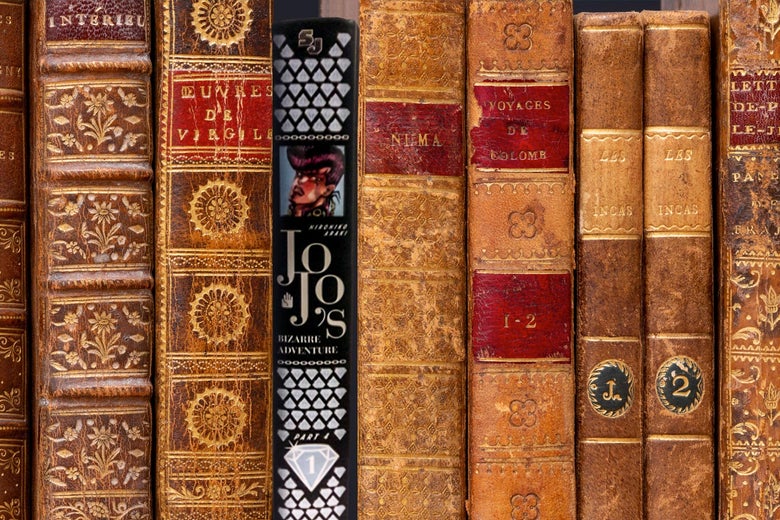

The creation of manga artist Hirohiko Araki, JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure has an over 30 year history. The manga premiered in 1987 and now spans eight parts, the most recent of which, Part 8: JoJolion, came out just last August. In the early ‘90s, an anime based on Part 3: Stardust Crusaders was released, but condensed the intricate plot into only 13 episodes; it largely slipped under fans’ radar. JJBA would not find true success as an anime until 2012, when the first and second parts—Phantom Blood and Battle Tendency, respectively—were adapted into a highly successful 26-episode series that is largely responsible for JJBA’s cult-like status today.

I was intimidated entering the JJBA universe. I have never been one for fandoms, and the countless memes—from “But It Was Me, Dio” to “How Does King Crimson Work?”— are a language all their own. The storyline itself is also, well, bizarre. JJBA follows various members of the Joestar family as they use their supernatural fighting spirits—called Stands—to defeat a series of increasingly outlandish Big Bads. What starts as a relatively conventional fantasy about a vampire pursuing world dominance evolves into a world where a line like, “There’s a shark in my soup! Get Trish inside the turtle!” makes complete sense in context.

Despite its absurdity, JJBA can connect to reality in its own way. One excellent essay about the series dissects its seemingly accidental queerness. A community of video essayists tackle everything from the thematic relevance of death in JoJo to the etymology of character names (Could Nijimura,which translates to “rainbow village,” be a reference to the Taiwanese street art exhibit?). The emotions in JoJo are often so sincere—loss handled with solemnity, friendships heartfelt and organic—that I projected my own feelings onto the show during my first watch. As I was finishing the Stardust Crusaders arc last year, I got teary-eyed over a storyline involving time travel; what I wouldn’t give to freeze time before things got any worse. Later, Jed became distraught when the once-strapping hero Joseph Joestar returned in Part 4: Diamond Is Unbreakable as a senial old man, a reminder that even the most dexterous bodies wilt.

But any metaphors one can infer feel like byproducts of the storyline. They are not the point of JoJo, if one can even say the show has a point.

The closest thing we get to the magna’s thesis comes from the character Rohan Kishibe, an eccentric manga artist who can peel off your skin and read the story embedded in your flesh (no, that is not a metaphor—that is literally his power). While licking a dead spider, Rohan quips, “Reality is the lifeblood that makes a work pulse with energy.” Rather than having fantasy serve as a lens through which to view reality, Araki uses reality to enrich his fantasy.

This is largely the reason why fans find JJBA so engrossing. Even as the narrative becomes increasingly ridiculous, the emotional core remains grounded. You’d be upset too if the magic dog with whom you shared a love-hate bond died while protecting you from the surrogate of a semi-immortal vampire. And who among us wouldn’t be enraged to learn that a vampire fused his head onto our grandfather’s dead body? You never feel foolish for becoming invested in this bizarre adventure, as Araki draws just enough from reality to make his universe pulse with energy.

I have tried to write about JoJo before. I have discarded countless drafts half-assedly relating the show to topical issues or examining its broader themes, like dying and the passage of time. These essays felt dishonest, like I needed some highbrow justification for loving this series. I’ve made peace with the fact that there really is no deep-seated intellectual curiosity driving my affection—my obsession is much more simple.

I love JoJo because you can lose hours debating which Stand is the most powerful (Heaven’s Door, obviously … ) or which JoJo is the best protagonist (it’s Josuke; fight me). I love JoJo because it’s set within a world where the first thing an immortal humanoid does after achieving his ultimate form is transform his hand into a demonic squirrel, and you think, “Yeah, that tracks.” I love JoJo because characters routinely dress in slitted crop tops and, despite their pants being held up by suspenders, their Versace thongs remain very visible—attire that’s well within the series’ realm of normalcy.

I love JoJo because it’s fun, and honestly? I haven’t had enough of that lately.

During Rohan’s first appearance, he claims he does not write manga for power or money or even esteem. He writes it for a very simple reason: “So that people will read it.” Araki has spent over 30 years doing the same thing, by telling a story that people keep wanting to read. This is a beautiful, not superficial, thing. Maybe Nero fiddling while Rome burned was less about flippancy, as scholars often suggest, and more the enduring desire for levity, even while the world’s on fire.

JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure is just a fucking story. That is exactly why I love it.

"story" - Google News

November 12, 2021 at 05:12AM

https://ift.tt/3bk1AIa

Maid on Netflix: the domestic works its story leaves out. - Slate

"story" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2YrOfIK

https://ift.tt/2xwebYA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Maid on Netflix: the domestic works its story leaves out. - Slate"

Post a Comment