I don’t much like the term narrative frame. It conjures up a box, angular and wooden, surrounding the inner narratives and keeping them in check. Of course that is literal minded and silly of me: narrative frames are really quite benign, not prisons, not even corrals, nothing like the stiff, gilded frame that holds a painting. What we call a framing narrative can open a story and leave before the story ends; or it can end a novel, never having participated before the last page.

If you take, say, Portnoy’s Complaint, Portnoy tells his tale to someone he addresses as “Doctor.” But it is only on the very last page, in a famous brilliant one-sentence chapter called “Punch Line,” that the doctor makes an appearance: “So [said the doctor]. Now vee may perhaps to begin. Yes?” Willa Cather’s My Antonia begins with the narrator recounting a conversation on a train ride with an old friend, a man named Jim. It is Jim who takes over the narration. His fellow passenger is never heard from again.

One of the reasons the word “frame” bothers me in this context is that the relationship of different narratives in a novel or short story strikes me more as a conversation. The narratives speak to one another, and, just as important, they listen to one another. Look at On Account of a Hat, a wonderful story by Sholom Aleichem in which a Jewish man, waiting for a train, accidently puts on an army officer’s hat and is treated with sudden, confounding deference and respect. When this humble shtetel Jew sees himself in the red-banded officer’s hat in a mirror on the train, he concludes not that he picked up the wrong hat, but that he’s left himself back at the station.

Certain accomplished novelists have a habit of giving themselves away which must often bring tears to the eyes of people who take their fiction seriously.Before telling the story, Alecheim the narrator reflects on the reliability of the fellow who tells him the tale:

“I must confess that this true story, which he related to me, does indeed sound like a concocted one … But I thought it over and decided that if a respectable merchant and dignitary of Kasrilevsky, who deals in stationery and is surely no litterateur—if he vouches for a story, it must be true. What would he be doing with fiction?” He adds, “I had nothing to do with it.”(112 Treasury of Yiddish Stories).

Aleichem the narrator then disappears except as a listener. “You hear what I say?” the other narrator keeps asking him. “And would you like to hear the rest of the story?” Like Roth’s psychiatrist, Aleichem the narrator is there throughout, but only to receive the story. The creator becomes the recipient, which is so often the result of a framing narrative. The reader and the narrator share the same spot on the carpet at the feet of the storyteller.

Anthony Trollope, who could not be more different than Sholom Aleichem except in genius and an underlying kindness to even the most bumbling of their characters, is another example of a writer who creates conversation and even friendship between narratives.

Trollope’s narrators, by which I mean, I suppose, Trollope, step back and send you on your way through landscapes, fox hunts, houses large and small, institutional envies, confusions in the mind of young men of folly, sense and determination and folly in young women, worldly wisdom or unworldly wisdom as well as folly in the aged; but Trollope, in the guise of his narrator, or his narrator in the guise of Trollope, keeps popping up, at seemingly random intervals, to interrupt his own story. This is the English accent of “You hear what I say?” But just like Aleichem’s shtetl storyteller, Trollope reminds you that this is a story, that the characters you have become so attached to and so intrigued by are “make believe.”

Henry James hated this quality of Trollope’s narrator. It struck him as almost sacrilegious.

How to create a strolling minstrel of a narrator in our post-post-modern culture? Just an easy-going, unself-conscious narrator?Certain accomplished novelists have a habit of giving themselves away which must often bring tears to the eyes of people who take their fiction seriously. I was lately struck, in reading over many pages of Anthony Trollope, with his want of discretion in this particular. In a digression, a parenthesis or an aside, he concedes to the reader that he and this trusting friend are only “making believe.” He admits that the events he narrates have not really happened, and that he can give his narrative any turn the reader may like best. Such a betrayal of a sacred office seems to me, I confess, a terrible crime.

But this haphazard narrator, this disruptive narrative crime, reappears, it seems to me, as if by the gravitational force of the narrative itself. The reader never feels a formal framework (perhaps because there is none; James, in his least vitriolic essay on Trollope says that Trollope “from the first, went in, as they say, for having as little form as possible; it is probably safe to affirm that he had no “views” whatever on the subject of novel-writing.”) What Trollope narrators offer the reader, instead, is a parallel, like-minded reader. James refers to the reader as a “trusting friend”; Trollope treats the reader as one.

The Trollope narrator often stays in the background because, presumably, he is as caught up in the story as we are. This ability to tell a tale and then disappear into that tale is what I find so mysterious and at the same time so reasonable, so welcome. That’s how stories are told when we tell stories to one another.

*

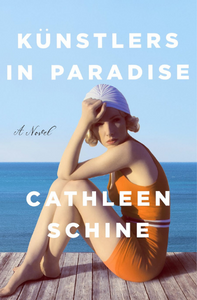

In the book I’ve just written, Künstler’s in Paradise, a lively 93-year-old tells stories of her adventures in L.A.’s émigré German Colony to a captive but increasingly enthusiastic audience, her 24-year-old grandson who is trapped with her in her Venice Beach bungalow during the 2020 lockdown. Her stories allowed me to explore the German Colony, a group of composers, writers and musicians who escaped the Nazis and landed in Los Angeles where they formed a close-knit group helping one another while out while bickering, gossiping and drinking strong coffee together.

I wanted to write about them, had to, really—these characters would not leave me in peace until I did. But how? How to keep the story from sagging into an over-researched, over-detailed, fussy, inauthentic historical novel? Stories within stories, the definition of a “narrative frame” novel. Or, perhaps, a “narratives in friendly conversation” novel?

My favorite Trollopian narrator is more elusive. How to create a strolling minstrel of a narrator in our post-post-modern culture? Just an easy-going, unself-conscious narrator? Nothing meta or formally self-conscious about it. That is, if not a lost art, then an art that often rushes away from contemporary writers with all the excited energy of a disobedient dog. At least, that dog runs off from me. The best I have been able to do is run after it, try to head it off, circle back, call its name, and eventually just wait for it to come trotting back covered with mud. And the odd tick.

__________________________________

Cathleen Schine is the author of Kunstlers in Paradise, available from Henry Holt & Co.

"story" - Google News

March 14, 2023 at 03:55PM

https://ift.tt/r3vThak

How To Find a Charming Narrator in a Self-Conscious Age - Literary Hub

"story" - Google News

https://ift.tt/4WDCywS

https://ift.tt/gHriAqw

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How To Find a Charming Narrator in a Self-Conscious Age - Literary Hub"

Post a Comment